In my last blog I explored the prehistory of an axe found in the West Kennet Avenue. Today’s blog continues with its more recent history, or rather the history of its finder, Mrs St George Gray. Whereas the previous blog drew much from existing archaeological knowledge of the British Neolithic, in this blog our sources are birth certificates, census records, and the diaries of WEV Young, a key figure in Avebury’s archaeological history who worked as a foreman on many excavations, including Keiller’s Avebury excavations, and later went on to become curator of the Keiller Museum. I am joined in writing this blog by Prue Saunders, Avebury Papers volunteer and a keen documentary historian, who did much of the digging into the history of Mrs St George Gray.

Before we proceed it is worth stating who it was Mrs Gray was married to, as this provides background as to why she was at Avebury. Her husband was Harold St George Gray (1872-1963), a distinguished archaeologist who began his career as an assistant to General Augustus Henry Lane Fox Pitt Rivers, who is often considered to be the father of British archaeology. Undoubtedly Gray learnt much during his time with Pitt Rivers, and he went on to become a respected excavator, noted for the quality of his draughtsmanship and the thoroughness of his publications. The beautiful marking on the West Kennet Avenue axe (see the previous blog) is in a hand that appears on much of the material from his Avebury excavations, and one suspects that it is the hand of Harold St George Gray himself, or perhaps Mrs Gray.

After working as Pitt Rivers’ assistant, Mr Gray spent a short period as an Assistant Curator in the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford before going onto the role that would define his professional life for the next 48 years, as the Curator of the County Museum of Somerset, and the Secretary of the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society. Throughout his career he was frequently in the field, excavating a series of important archaeological sites including the Iron Age Lake Villages at Glastonbury and Meare, and the Neolithic henges of Arbor Low in Derbyshire, Maumbury Rings in Dorset, and of course Avebury.

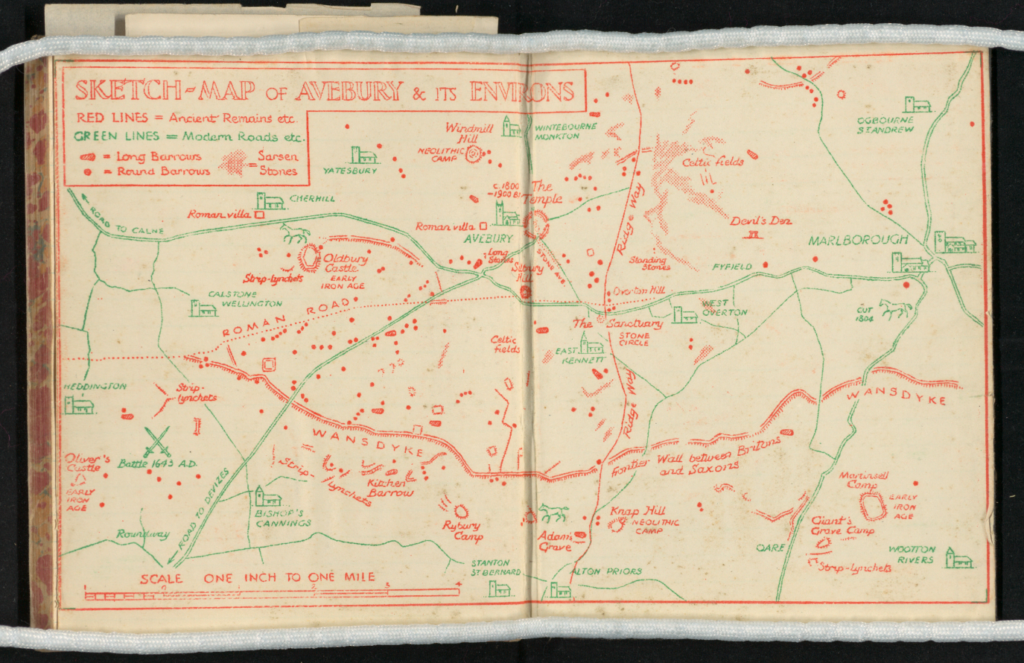

Gray’s excavations at Avebury remain the only largescale investigation of the henge’s massive ditch. The current form of Avebury’s ditches is the result of many millennia of silting, and although they still appear massive, their true scale is almost impossible to appreciate. Their excavation was, by any reckoning, a mind-boggling undertaking which produced one of the most iconic photos of any British Neolithic excavation. Mr Gray’s excavations at Avebury took place in 1908, 1909, 1911, 1914, and 1922, and it was in 1911 that Mrs Gray found the axe somewhere along the line of the West Kennet Avenue: and so, we return to the true subject of this blog.

Documentary research readily reveals that Mrs St George Gray was Florence Harriet St George Gray (née Young). She was born in 1875 to a farming family in Staffordshire, and moved to Motcombe in Dorset when she was three or four years old. The second of seven children, her family was listed in the 1881 census as farming 50 acres and employing one farmhand and two servants. They were, therefore, relatively comfortable, if not wealthy, by the standards of the day. In 1899 Florence Young married Harold St George Gray at her local parish church at Motcombe. In 1901, when Harold was Assistant Curator at the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, their son Lionel St George Gray was born. He sadly died in 1923 aged 22 with his profession listed as an “archaeological student” on his death certificate. Florence St George Gray outlived her husband, who died in 1963, remaining in the home they had retired to, Treasurer’s House in Martock, Somerset, until her death in 1970.

Those are the facts of Florence St George Gray’s life as revealed by public records. To find out more about her and the role she played in her husband’s excavations we need to turn to archaeological archives, publications, and the diaries of WEV Young (no relation to Florence’s family, as far as we are aware). What is immediately clear from even a cursory view of these sources is that she was almost ever-present in her husband’s fieldwork, as was, one suspects, their son Lionel.

One of the benefits of the fact that archaeologists are generally very good at keeping photographic records of their excavations is that we often get to see snapshots of the people who were in and around those excavations. Often these images are working shots of people digging, or we see visitors incidentally in the background of shots of excavation trenches. Harold St George Gray’s photographic archive of his Avebury excavations includes many of these types of shots. A little more unusually, they also contain rather more formally posed portraits of a well-dressed woman, sometimes accompanied by a young boy. Often the female figure appears, somewhat ethereally, in the middle distance in a manner reminiscent of a landscape painting.

Mr Gray wrote long notes on the back of his photographs detailing their subject. In the photo below he describes the scene in detail, including observations about a bird’s nest perched in a recess in one of the stones, and even whose garden he is standing in to take the photo. The one thing he does not do for any photo, however, is mention the presence of the woman or the boy! Still, we can be relatively certain that the figures are Florence St George Gray and her son Lionel.

In the earlier part of the 20th century, the role of an excavation director was to observe, direct, and record. Getting one’s hands dirty shifting tons of ditch fill was the work of labourers and site foreman. One can imagine that in between the moments when his presence was required in the trench, Mr Gray and his family were free to explore the surrounding landscape, or indeed to enjoy a spot of breakfast! We are provided insight into this in an account of the discovery of a skeleton in the Avebury ditch detailed in Harold St George Gray’s publication of his Avebury excavation, in which he recalls:

“The writer’s absence at breakfast was also unfortunate, for on his return some of the bones [of the skeleton] had been removed, and the skull had apparently been trampled upon before any part of it was actually recognized by the workmen engaged on this spot. Some of the bones had been thrown back: these, however, were collected, the picks were set aside, and the clearing of the interment and the surroundings was then carried out by Mrs Gray and the writer.”

- Gray, 1935, p. 145.

One can quite imagine the dressing down the poor workmen were given upon Mr. Gray’s return. The passage is most interesting, however, because it reveals that, as well-dressed as she appears to have been at all times, Florence Gray was very much involved in the process of excavation, and was trusted to undertake delicate tasks unsuited to ‘clumsy’ workmen. In many respects, it seems that Mr and Mrs Gray worked closely together in regard to the excavation and processing of the excavated material. As C. A. Raleigh Radford recalled in Mr Gray’s obituary in the Proceedings of the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society, “Mrs Gray was throughout his principal helper in all his activities, including his excavations”.

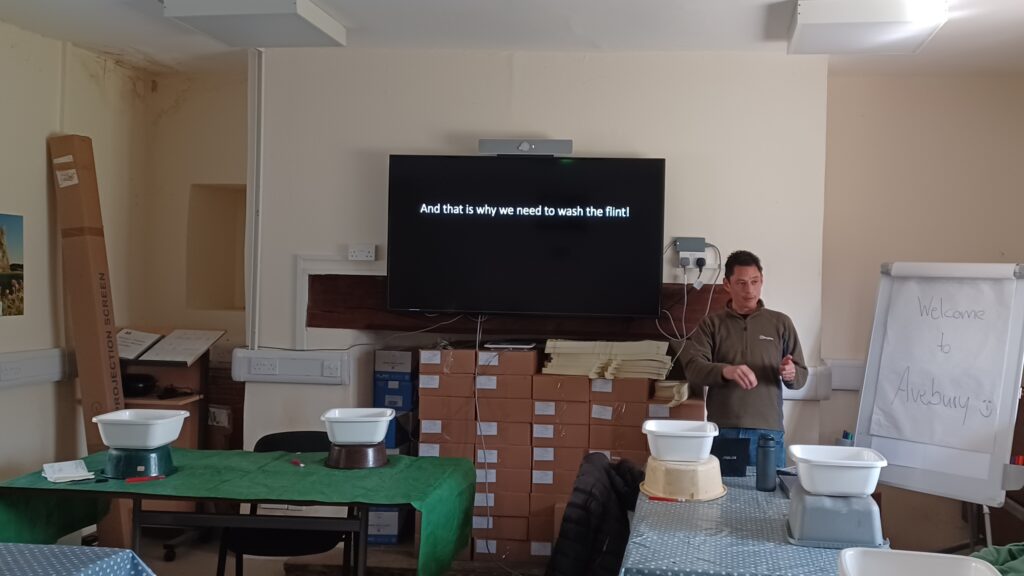

In the 1921 census, at the age of 46, Mrs. Gray for the first time records her occupation on her return as a Curator’s Assistant. In Mrs. Gray’s obituary, Cookson details “half a century of dedicated service” that she had provided to the Someset Archaeological and Natural History Society. This included copying minutes of meetings, supervising volunteers to wash finds, restoring museum exhibits, and driving her husband around to visit archaeological sites.

The extent to which Mrs Gray was ever-present in her husband’s working life is also suggested by the diaries of WEV Young, who met the Grays numerous times through his work as an archaeological foreman. These days we would think of the role simply as that of an archaeologist, or perhaps an archaeological supervisor, but in the earlier 20th century a foreman, despite often being a highly talented and knowledgeable excavator, stood somewhere between the workmen and the archaeologist. There was certainly a hierarchy at play in such roles, and according to Young’s diaries, this was a status quo that Mrs Gray was quite keen to maintain.

It should be stated that our observations are of course very much from the perspective of Mr Young, and we have no diaries from Mrs Gray to provide a counterpoint to his perspective. Bearing that in mind, in the few times that Mrs Gray appears in his diaries there is a clear enmity between the two of them, mostly based around Florence Gray establishing their relative social positions. In one entry, reflecting on his work during Mr Gray’s Lake Village excavations, Young notes:

“Mr Gray called me into the hut at five o’clock and paid me off, remarking as he did so that funds this time were very short (I hope he will get enough for his own “honorarium”). Mrs Gray also joined in with a few well chosen remarks, plainly intended for my edification, although addressed to her spouse – “Really dear: I cannot keep on making up the expenses of the excavations, my purse will not allow it. I had to make up five pounds for the Ham Hill work.” … In the presence of Sir Joseph and Lady Bowley, I listened meekly to all this … behaving myself with that gruelling humility one should do, in the presence of their superiors, then touching my ragged cap I backed away, and took my leave.“

- WEV Young Diary 2, Tuesday September 23 1930, p. 129-131.

Assuming the veracity of the account, Young’s rather sardonic attitude to the class system that prevailed at the time is clear. Equally clear is that, perhaps unsurprisingly, Florence Gray was keen to foster the elevated social status that her husband’s position gave their family. Perhaps more notable is that fact that she was not only actively involved in her husband’s excavations, but to some extent she partly funded them too, and she was keen to let others know this was the case! Her obituary suggests that alongside making up the shortfall in expenses from her own purse, she also raised money for her husband’s excavations.

Hopefully, through the course of this blog, we have managed to breathe some life back into a figure that has stood at the periphery of Avebury’s history. This seems fitting, as Florence St George Gray certainly does not appear to be someone who was content to remain on the periphery. Rather, she and her husband appear very much to have worked as a team, or perhaps, instead of a team, we should better think of them as a couple with common purpose. When I first came across the axe in the stores, I wanted to bring Mrs Gray out into the light because I felt that being known only as the wife of a noted archaeologist was doing her a disservice. Having spent quite some time trying to write about her, I wonder whether my desire was wrongly guided by modern sensibilities. I suspect that, as strong a character as she appears to have been, she was also keen to uphold the social norms of the day, and was probably quite proud of being Mrs St George Gray.

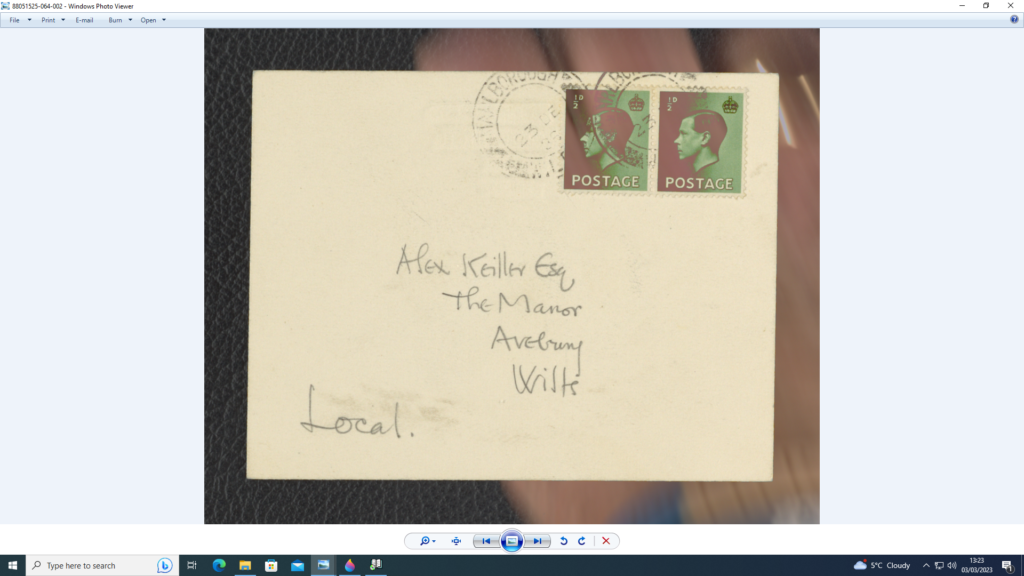

To bring things full circle, we will finish our account of Florence St George Gray with a particularly apt photograph. It is a photograph of Mrs Gray on the West Kennet Avenue taken in 1908, 3 years before she came across an axe somewhere probably not too far from where the photo was taken. Incidentally, WEV Young’s diaries tell us that the Grays visited Keiller’s excavation of the West Kennet Avenue in 1934, the year he excavated the West Kennet Avenue Occupation Site. One wonders if Mrs Gray told Keiller of the axe she once found on the Avenue…

Sources:

Gray, H. (1935). VI.—The Avebury Excavations, 1908—1922. Archaeologia, 84: 99-162. doi:10.1017/S0261340900013655

Ralegh Radford, C. A., and Rawlins, S. W. (1963). Harold St. George Gray, 1872 – 1963, Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society, 107: 111-116.

Cookson, C A. (1970). Mrs. St. George Gray (née Florence Young) 1875-1970, Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society, 114: 122.

WEV Young’s diaries are held at the Wiltshire Museum, Devizes, Accession number DZSWS:MSS.4269