The inspiration for writing this blog came from finding an axe whilst trawling through the archive of weird and wonderful objects held in the Alexander Keiller Museum at Avebury.

Most of the objects in the museum were found during archaeological excavations and are boxed along with crucial information on which excavation they were uncovered by, and the cutting (excavation trench) and context (e.g. stone-hole, ditch, pit etc.) in which they were found. A smaller number are what we often call ‘stray finds’. These are finds that were found by chance, for example in a molehill or on the surface of a ploughed field, and therefore have little contextual information to go with them.

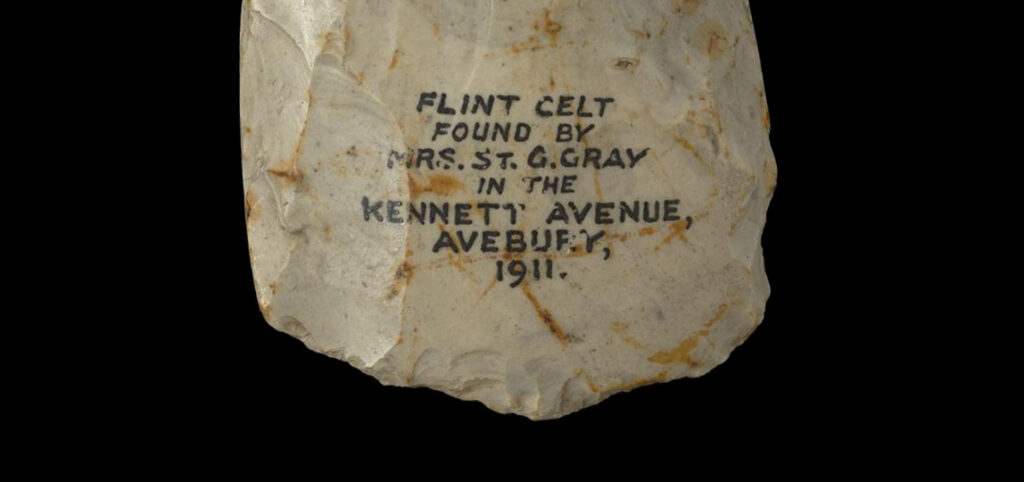

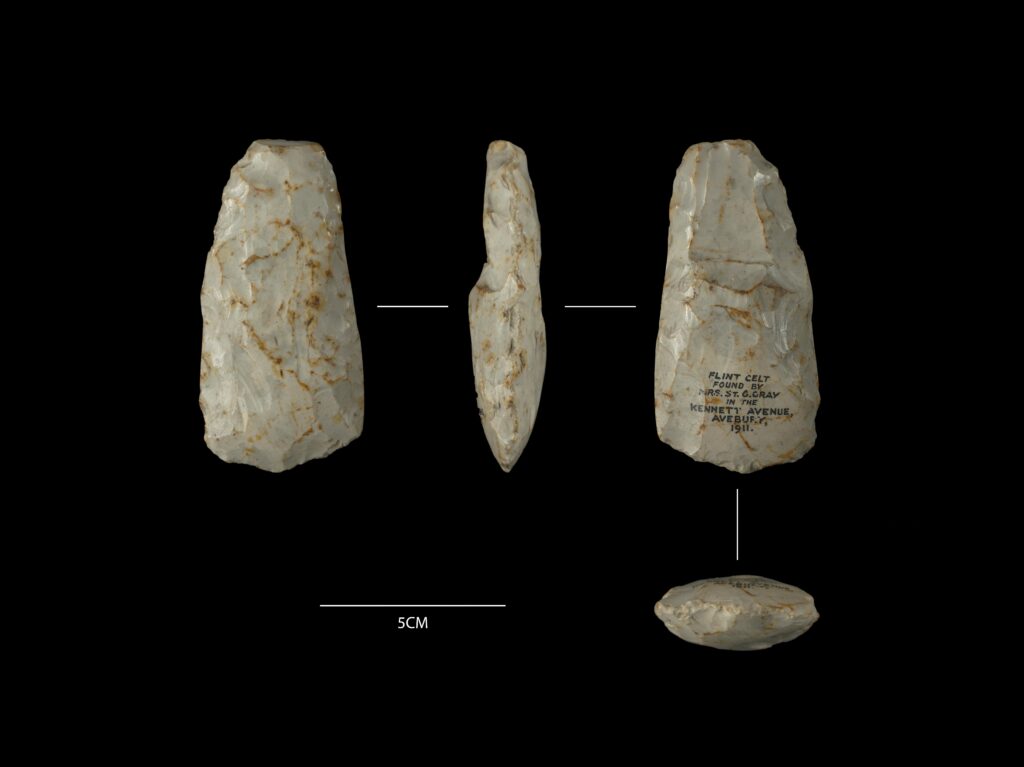

The axe in question was one such find. It was stored by itself in a small cardboard box, and all the contextual information we know about it is written on the object itself. The writing on it simply says:

“FLINT CELT FOUND BY MRS. ST. G. GRAY IN THE KENNETT AVENUE AVEBURY 1911”.

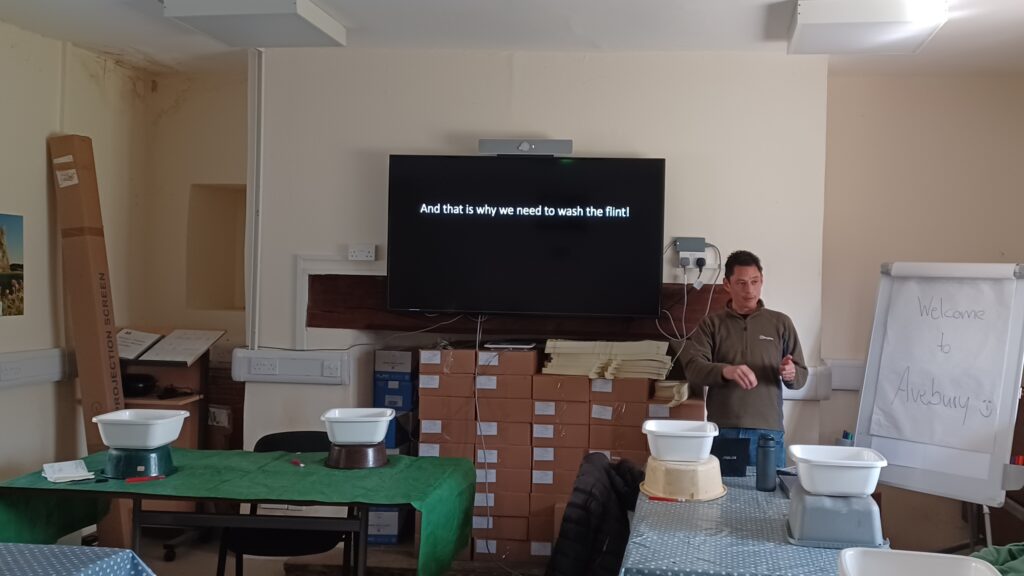

Part of my job on the Avebury Papers Project is to catalogue all of the finds from Avebury that are held by the Keiller Museum. As a result, finding the axe hidden away on a shelf raised a few crucial questions for me. Some were basic ones, such as: what is the object, how old is it, and exactly where was it found. The latter question is essential. To archaeologists context is everything. Individual objects can tell us lots about past societies, but they hold a lot more value when considered as assemblages of objects, particularly if we also know what type of context they came from. An axe found in a midden might mean something quite different to one formally deposited into a pit. Beyond these relatively prosaic questions, there are other interesting questions that we can pose of this particular object, namely, who was Mrs St. George Gray, and how did she come to find the axe. I am going to attempt to answer as many of these questions as I can in the course of this blog.

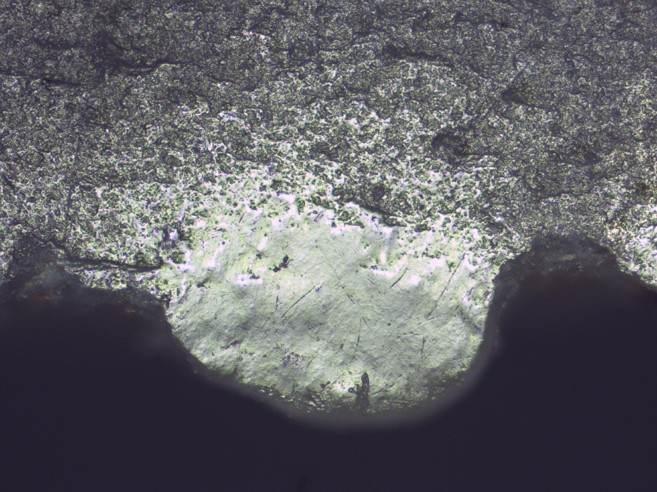

The easiest of these questions to answer relate to the type and broad age of the artefact. The object is a ground and partly polished flint axe dating to the Neolithic period. This means that the axe was first flaked into a rough shape, and then finished by a combination of grinding and polishing of its surfaces. Sometimes the grinding of an axe’s surface covers the whole of the axe, sometimes it is patchy, covering the ridges between flake scars that stick out the most. Almost always, the grinding and polishing covers the cutting edge where it is used to create a sharp and durable edge suitable for working wood. Along with first appearance of pottery, and the construction of monuments, axes of this type are one of the defining features of the Neolithic in Britain (c. 4000 to 2400BC). Actually, all of these things occur in different parts of Europe in the preceding Mesolithic period (albeit not commonly), but that is a subject for another blog!

Polished flint and stone axes are regular finds on Neolithic sites, occurring from the start of the Neolithic up until the earlier part of the Late Neolithic. They occur most frequently on Early Neolithic sites, such as the Windmill Hill causewayed enclosure located 2km to the northwest of Avebury. Much closer to Avebury, flint axes also occur, albeit in smaller numbers, amongst the predominantly Middle Neolithic (c. 3500-2900 BC) artefact scatter known as the West Kennet Avenue Occupation Site. The occupation site lies on the line of the West Kennet Avenue and was first excavated in 1934 by Keiller and his team (see this blog post for details). The 1934 excavations yielded roughly 15 axes and adzes, with Isobel Smith noting in the excavation’s publication that partly polished and unpolished axes and adzes were the characteristic form of the assemblage (as in the photograph below).

So, the axe found by Mrs St. George Gray could certainly fit within the assemblage from the West Kennet Avenue Occupation Site. This is significant given that all we know of its find spot is that it was “in the Kennett [sic] Avenue”. It may, therefore, seem likely that it came from the West Kennet Avenue Occupation Site, but given that the Avenue itself is just short of 2.5km long it is worth considering whether it came from somewhere else along its length.

We can safely assume that Mrs St. George Gray is the wife of Harold St. George Gray, who excavated Avebury from 1908-1922. Given that the axe was found in 1911, the axe was most probably found by Mrs St. George Gray whilst her husband was excavating. But that doesn’t make deducing a more exact location of the find any easier.

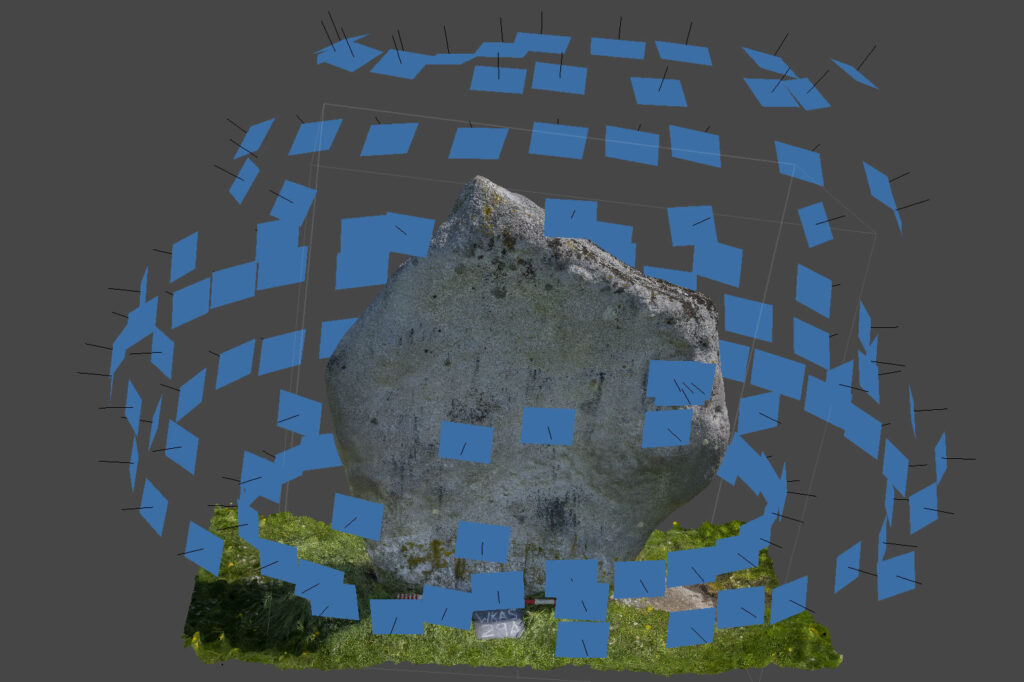

We know that during the Gray’s excavations at Avebury only 19 of the West Kennet Avenue stones remained visible. The antiquarian William Stukeley had recorded 72 stones in 1722, and the Grays were clearly aware of his description of the course of the West Kennet Avenue. In Mrs St. George Gray’s time, as today, the most visible part of the Avenue was its northernmost third where it reaches Avebury. In 1911, however, even in this stretch, many of the stones were buried, awaiting their re-erection by Keiller’s team in 1934 and 1935.

What we also know, thanks to the recent excavations of Josh Pollard and Mark Gillings, is that this stretch of the West Kennet Avenue was rarely ploughed, with the artefact scatter that makes up the West Kennet Avenue Occupation site lying a good depth under the topsoil. This means that it is unlikely that Mrs Gray would have come across the axe kicking around on the surface, unless it had been fortuitously brought up in a molehill, something that does happen on occasion.

Another possibility is that she found it whilst tracing the route of the Avenue in the field immediately south of the currently reconstructed part of the Avenue, a field which we know has been regularly ploughed in the past. It is also possible that the axe was found further from Avebury as the Avenue winds its way towards the Sanctuary, but this is perhaps less likely given how interrupted the remaining stones of the Avenue are in this part of its route, and therefore how less certain it would be that it was found “in” the Avenue.

Hopefully it is not too anti-climactic, but that is all we can deduce about the find spot of the axe. It is a significant find, but it would be a lot more so if we could be certain about exactly where it was found, and particularly whether it was part of the West Kennet Avenue Occupation Site, or potentially some other concentration of features or artefacts along the route of the Avenue.

We are left with two possibilities. Either it was found, most likely in a molehill, in the extant northern third of the Avenue, or it was found further to the south, probably in a ploughed field in a location where it was still possible to confidently establish where the line of the Avenue was. Either is possible, although I am somewhat in favour of the idea that the axe was part of the West Kennet Avenue Occupation, found by Mrs Gray some 23 years before Keiller’s discovery of the site. Unfortunately we will never know the truth. If nothing else, the story highlights the importance of accurately recording the find spots of stray finds!

Having dealt with the archaeological significance of the find, we can now turn to the finder herself. Up until now she has only be referred to as ‘Mrs St. George Gray’. This has not been to diminish her individuality or personhood, rather it is a simple reflection of the fact that when I started writing this blog that was all that I knew of her. Indeed, that was all that any of the current crop of Avebury archaeologists knew of her. In the literature, she is very much in her husband’s shadow. Even in her husband’s obituary published in the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society in 1963 she is only referred to as Mrs Gray. Uncovering the hidden histories of people involved in the Avebury excavations is very much at the heart of the Avebury Papers Project, and so along with investigating the possible find spot of the axe, its discovery in the archive prompted me to find out all that I could of Mrs St. George Gray. For now, though, this blog is getting rather long, so the identity of Mrs St. George Gray will have to wait for the next post…