While transcribing Denis Grant King’s journals, it has struck me how little mention there is of tensions in Europe caused by Hitler and Germany. Of course, my view comes with the gift of hindsight with full knowledge of the tsunami that is about to crash across Europe in the form of the Second World War.

I am now transcribing pages covering spring and summer 1939, and with the exception of the one or two mentions of problems caused by soldiers out on manoeuvres, and occasional musings on war and politics, relatively little has been mentioned of the looming threat of the UK going to war – that is until 26th August. In the journal entry for this day there is mention of some of the steps people were suddenly making, obviously dreading (or expecting) a turn for the worse.

In the journal, it is unclear what discussions had happened at Avebury on this particular day, but the impending war had clearly become enough of a cause for concern for two things to happen. The first was that Alexander Keiller, who considered war to be “imminent”, asked his excavating staff to continue working on the Saturday afternoon to complete recording features and records before the government “called up all the men” for military service. The second thing was that two individuals, Commander Rupert Gould and Leslie Grinsell sent valuable manuscripts to Alexander Keiller so they could be kept safely at his Avebury museum. Commander Gould actually visited Avebury to hand his manuscripts over personally as he travelled to Bath to take up duties at The Admiralty.

For those wondering what significant event happened on 26th August 1939, it was what is referred to as the “Jabłonków Incident” when German agents tried to take over the Jabłonków Pass, a strategic railway tunnel, in order to help Germany’s invasion of Poland. However, the Germans were fought off by Polish soldiers and the planned invasion was postponed.

On September 1st, the German Luftwaffe started bombing Poland including the town of Katowice, where a young reporter for the Telegraph newspaper called Clare Hollingworth was staying. Clare was a remarkable persona and is known as being the first woman to be a war reporter. Witnessing the bombing raids first hand she tried to alert the authorities but Polish leaders and the Second Secretary at the British Embassy in Warsaw refused to believe her urgent phone calls; after all, negotiations were still ongoing. Later, she saw first-hand thousands of German troops and tanks lined up across the border, facing Poland. It was only when she reported it and the Telegraph ran the story that the British public at large realised what was happening.

1053 miles away from Katowice, the lives of the people Avebury would quickly change.

DGK mentions a news report – which is likely the one by Clare Hollingworth – and writes that war will be declared in the next couple of days. The government thinks, upon declaration of war, the Germans will carry out a huge bombing campaign. Children in the cities are soon transported to the country, and a bus load of 70 children from the East End with their teachers arrives in Avebury. DGK arranges for his parents to join him. By 2nd September, Black Out precautions are put into place.

Avebury, along with the rest of UK, is bracing itself for war.

**

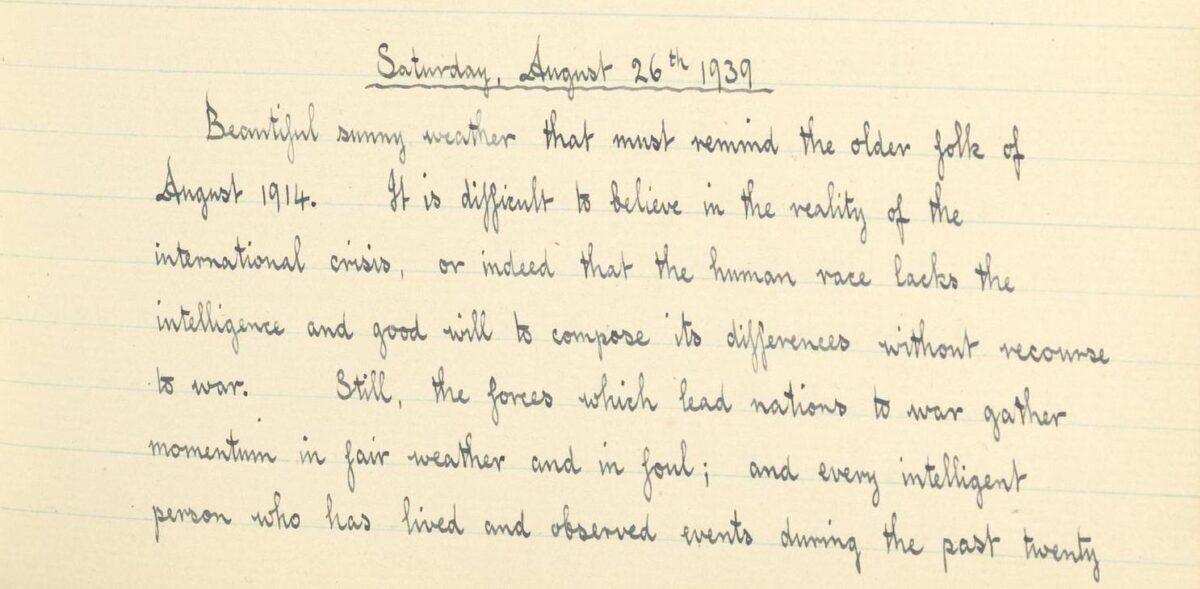

The full extract for Saturday 26 August 1939, from Denis Grant King’s diary, Alexander Keiller Museum Accession Number 1732624-003.

“Saturday, August 26th 1939

Beautiful sunny weather that must remind the older folk of August 1914. It is difficult to believe in the reality of the international crisis, or indeed that the human race lacks the intelligence and good will to compose its differences without recourse to war. Still, the forces which lead nations to war gather momentum in fair weather and in foul; and every intelligent person who has lived and observed events during the past twenty

years would be unduly sanguine if he had not expected another holocaust sometime. The question is, when?

No doubt statesmen will try to put it off as long as possible, that is, as far as delay is consistent with imperial interests. Churchill suggested that the zero hour would occur in August.

Anyway, Alexander Keiller believes that war is imminent and has asked us all to continue work on Saturday afternoon to reveal the “Z arrangement” as much as possible, and complete the records, before the Government calls up all the men.

Another reminder of 1914 came in the person of Commander Gould, R.N., who fought at the Battle of Jutland. He was then on his to way to Bath to take up duties under the Admiralty and called in at the caravan, where Alexander Keiller introduced him to me. He is a six foot man, 18 stone, so he says, clean shaven and grey hair; also very friendly and talkative, giving an account of various talks he had broadcast from the B.B.C., mostly, I understood, of an informative character on a variety of topics.

His object in calling was to leave certain manuscripts of value to be deposited in the Museum, which he considered to be a place of comparative safety. L.V. Grinsell also sent us some of his MMS [manuscripts] for safe keeping.

After Commander Gould said good-bye, Alexander Keiller told me a little about him. It appears that after the War was over, his wife left him, and his distress affected him mentally, so much so that he lost his job and sank into very low water. He then spent ten years perfecting the Harrison chronometer and making it work (which apparently it never did before), for which service the government rewarded him with the paltry sum of £100. One should see his work in the Greenwich Naval Museum. A queer story. One would not have thought that such an immense robust fellow could have been so upset by a little bit of fluff; but that is life!”