Content note: please be aware that this post contains reproductions of black-and-white photographs of medieval human remains excavated and photographed in-situ at Avebury in the 1930s. The blog also contains descriptions of how the individual is thought to have died.

Introduction

I am a current student of Digital Archaeology at the University of York. The subfield of Digital Archaeology is a relatively new phenomenon, including all aspects of archaeological investigation that might include the use of computers or software. Digital archives, 3D modeling, VR, Geographic Information Systems and more are all aspects of what a digital archaeologist may do, but it certainly does not cover the entire spectrum.

I began my placement with the Avebury Papers project in January 2024, where I have been able to explore what it means to help build and participate in a digital archive. Having worked in some manner of physical archives in the past, it has been an incredible experience to see the difference between the physical and the digital, and how these different experiences and environments necessitate different approaches not only to archiving, but in facilitating the use and exploration of an archive.

During my placement, I was tasked with getting to know the archive by exploring the catalogue in progress and digitised items; selecting items to create a Pathway into the archive for future users; and creating a user guide which explains the transcription process.

Exploring a Digital Archive-in-progress

The Avebury Papers provides a unique opportunity not only to explore the fascinating henge monument, but also the many different strands that make up an archaeological excavation. The archive includes 1930s excavation diaries, by Alexander Keiller, William Young, and Denis Grant King, and all of the bureaucratic documents that go into facilitating excavations. These materials are important facets of knowledge production that are often overlooked when considering an archaeological excavation. Not only do they provide researchers with a framework for further investigations of the site as time goes on – and how a site can be excavated and revisited over the course of one-hundred years – but it showcases a window into the past. It highlights the human experience of the archaeological excavation, rather than showing off the artifacts that we are used to seeing on display in museums or stores.

There are issues with digital archives of course. And there are especially issues for encountering a digital archive which is not finished yet. As part of my placement, I have been accessing the digital photographs of archival materials and spreadsheets of information via a Google Drive, in formats that are far from the finished interface.

There is an inherent disconnect between seeing a tangible item and place in the real life world and viewing a virtual archive through an accession number and a screen. Digital items are looked at largely in a vacuum, in their own ‘window’ on the screen – this is counter to how you might view an artifact in a section of a museum, where it is contextualized with multiple others right next to each other.

Take Figure 2 for example. Here we have two photographs documenting the excavation of human remains within Avebury stone circle during 1938. Looking at the hand-written description, it reads:

“Photograph showing how the barber was trapped by the accidental falling of stone No 16. His pelvis was smashed and his neck broken, while his right foot was wedged beneath the stone.”

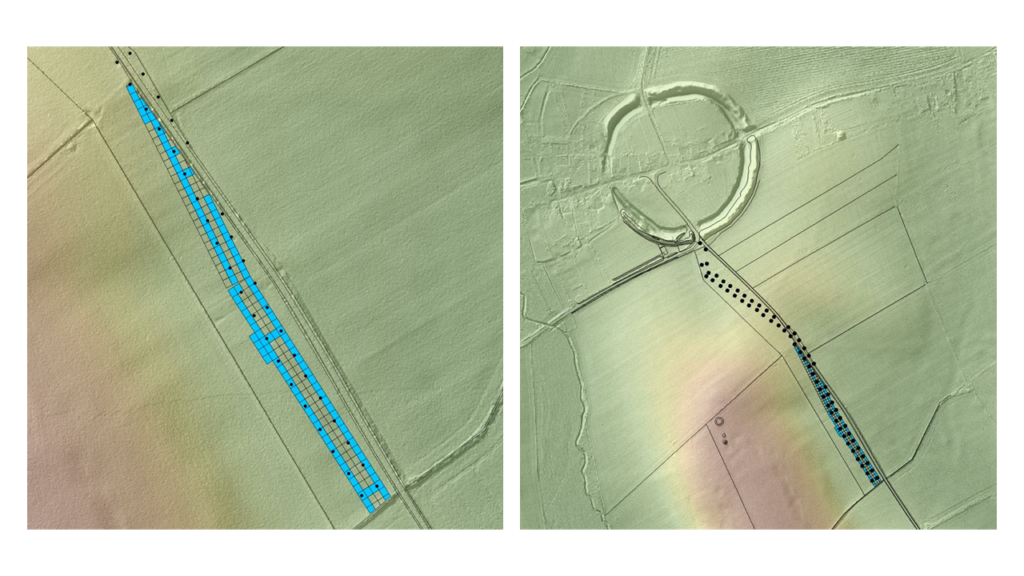

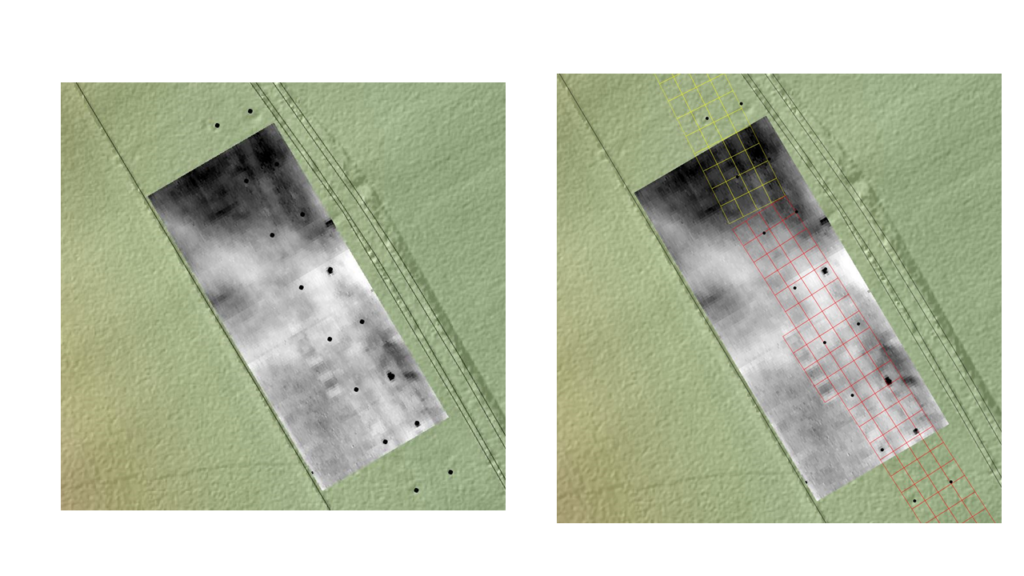

From this photo and the general context of the Avebury Archive, you may guess a few things: that this individual could have been one of the prehistoric denizens of Avebury amidst its construction, and they were killed by the movement of the stone. Encountering only this photo set in the archive will not shed much light on the role this individual played in the story of Avebury.

However, when you add context with the words of an expert who was part of the excavation team, the image becomes much more clear – as seen with Figure 3, below.

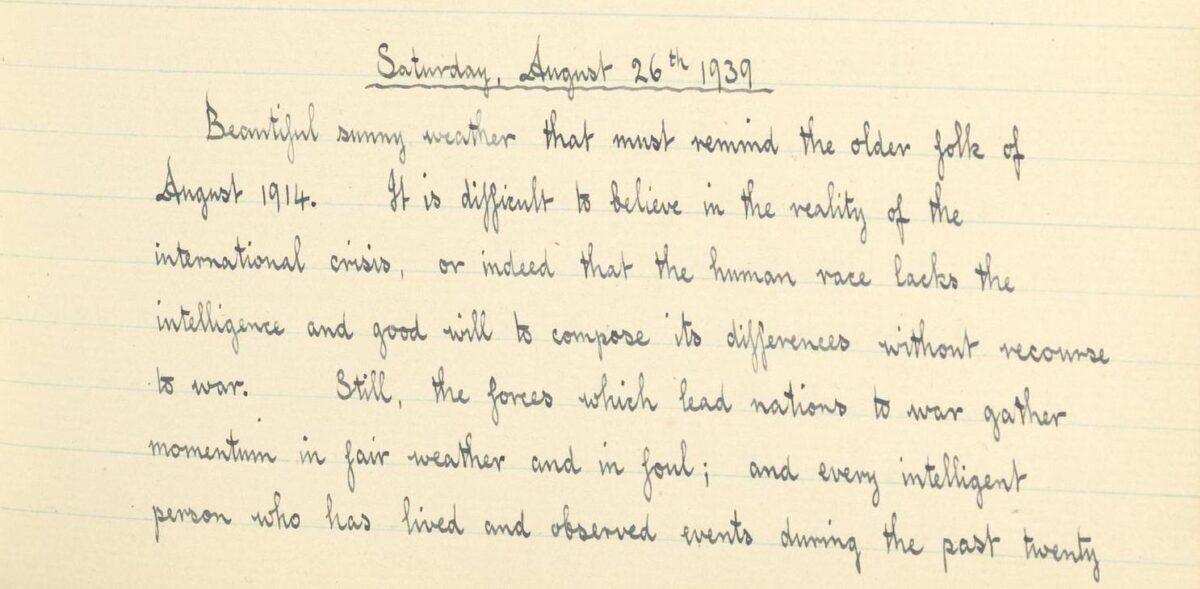

Figure 3 is an excerpt from the diary of Denis Grant King, with a key passage on the right hand page:

“Thursday, September 15th 1938.

To the Museum. It now appears that the medieval skeleton found partly crushed under a large megalith in the south west-sector is not that of a tailor, as I had been told, but of a surgeon barber, aged 30 to 35, of the time of Edward I or slightly later. Three silver pennies of Edward I, a pair of scissors with sharp (not angular) points, a probe or lancet, and a buckle were were found with the skeleton. I saw these exhibits laid out on the table in room behind the museum in preparation for exhibition on the morrow. On the site I noticed that the “barber” stone was now standing without any baulks of timber, and the next stone had been re-erected. The base and verticality of this stone were determined this morning ready for fixing with concrete socket.”

Transcription from Denis Grant King’s diary, accession number 1732623-001, spread 60.

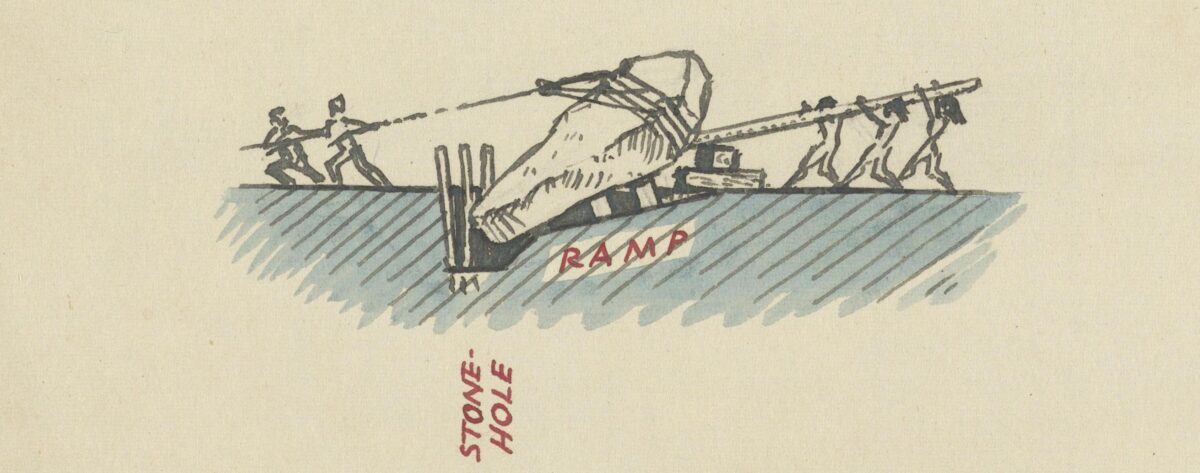

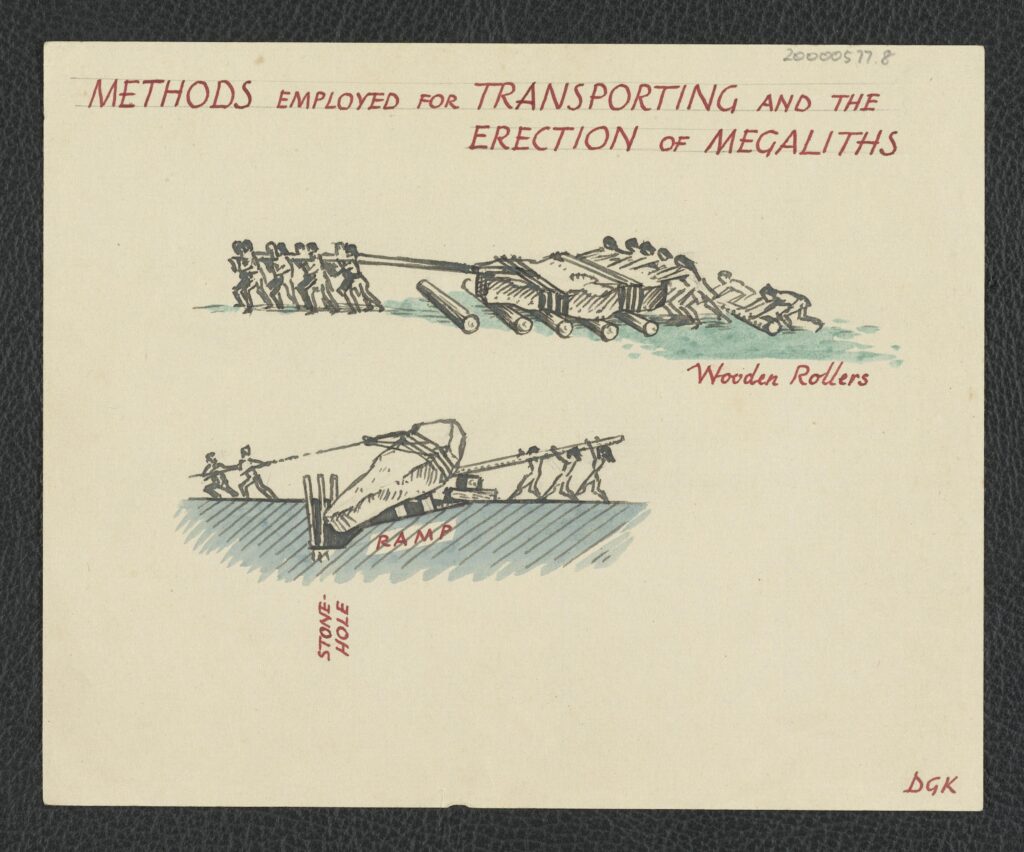

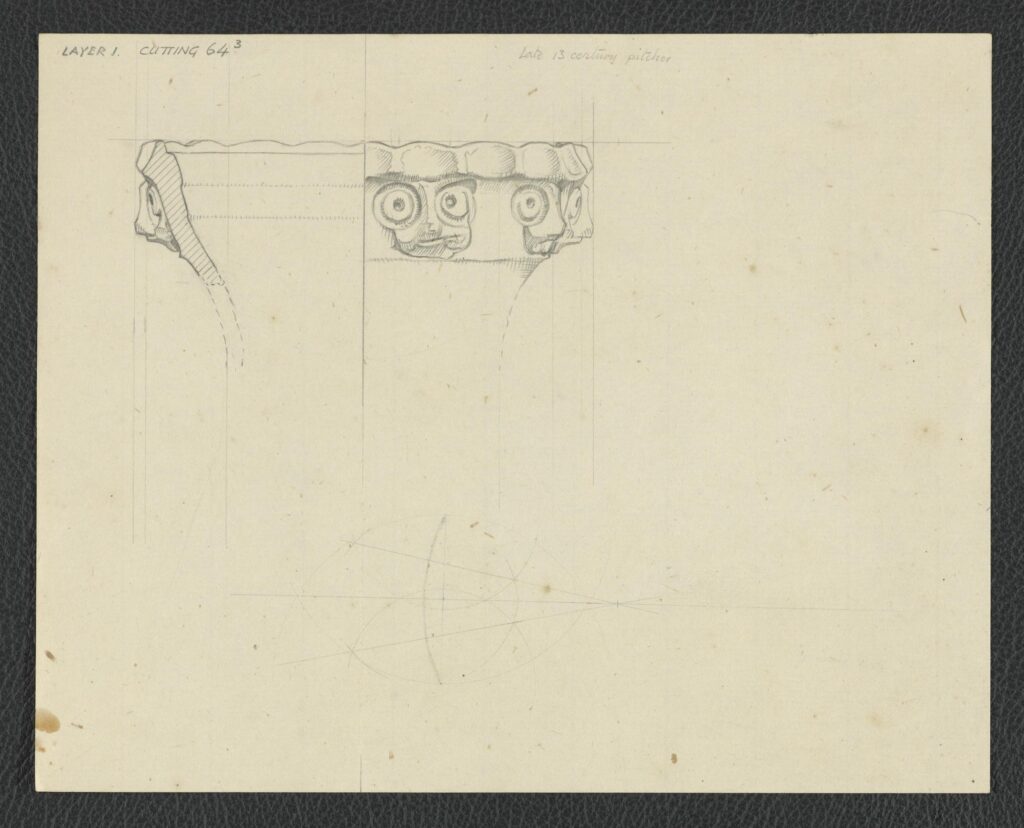

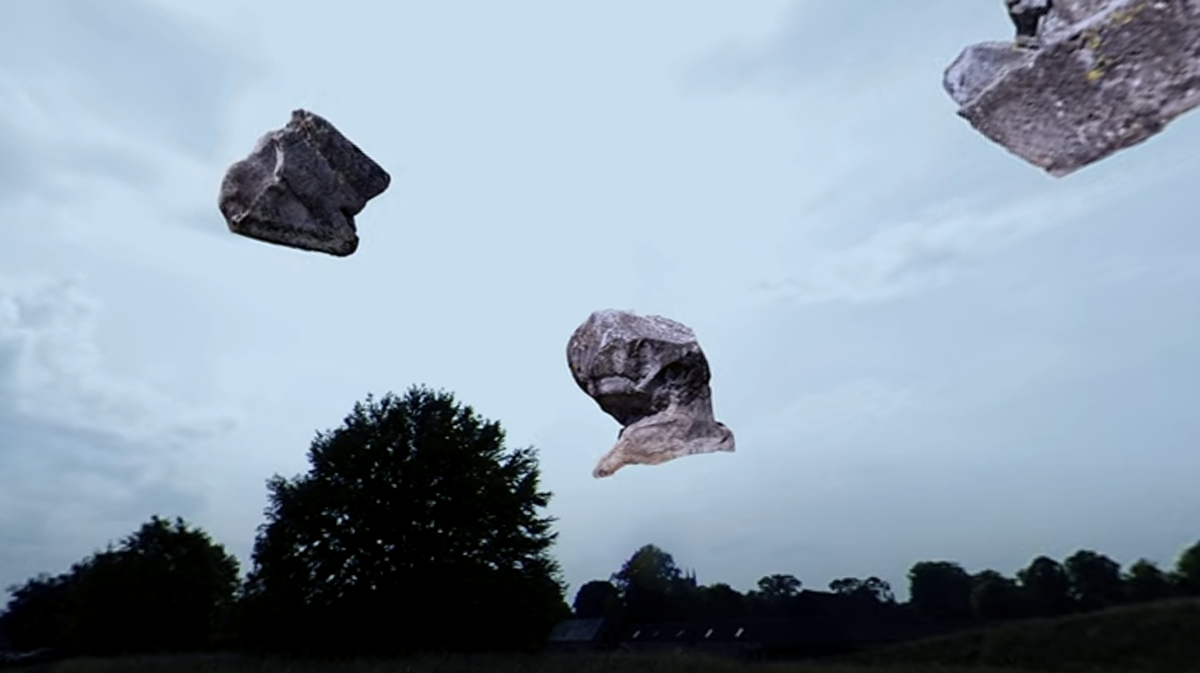

When working your way through a digital archive which does not yet have a complete catalogue, you sometimes have to build that context yourself. Archives like the Avebury Papers, that house both the written reports and diaries of the excavation as well as the artifacts and features that were found, provide a great way to pull together a story. To orient myself in the digital archive-in-progress, I started by seeking out images that spoke to me the most – one of these was Figure 1. I save these photos and then read through some of the transcriptions of diaries that accompany the artifacts, specifically looking at similar dates. This is how I was able to build context for myself within the archive.

When the digital archive is finished, users will be able to perform more complicated searches. However, this task can still be laborious, and also is not always an accessible option: after all, a user would have to have a keyword in mind, or already know what they are looking for if their only way into the archive is a search box. Someone that is a casual viewer of an archive, who might not be trained in archaeology or history, may find this process of searching cumbersome. Some users may prefer to have context laid out for them more ‘generously’, rather than having to search for it themselves (Whitelaw, 2015). Therein lies one of the challenges of making an open, exploratory digital archive – and why building a Pathway into the archive is an important task that I was given as a Placement volunteer.

Creating a Pathway: with Denis Grant King

My main objective during this placement was to prepare a new pathway into the archive: that is, establishing themes and contexts that users might find helpful to follow to make their journey into the archives a more streamlined experience. By building a Pathway into the archive, I was able to do a few different things. One of these is building an engaging and entertaining introduction into one aspect of the archive, giving a user something to get started with research in the archive itself. In this case, I chose materials produced by Denis Grant King, an archaeologist and draftsman for Alexander Keiller, the man running the excavation. Second, this Pathway also allowed me to contextualize various aspects of the archive. The photographs of the barber surgeon excavation and the diary entry I shared above is one example of how I brought together archival objects for the pathway, giving more contextual information and a story for the black and white photographs.

You can read more about the Pathway that I created, and the feedback generously shared by Avebury National Trust volunteers that helped with its development, in my second blog post [ed note – coming soon!].

User Transcription Notes

I also have been working on user transcription notes. The archive itself has plenty of handwritten diaries – many of which are difficult to read. Transcriptions make the process of exploring them – whether for research or pleasure – much easier. For example, transcriptions allow for the use of the search function on a web page, wherein you can search for key phrases of interest. However in transcribing these texts, decisions must be made on things to change or keep the same.

User notes, then, provide a guideline for archive users to follow that will explain any changes that have been made to the text for legibility’s sake. Eventually, the archive will house user guides of various kinds to help people to understand both how to navigate the archive, but also how the archive in its digital form was created. These guides will hopefully make the archive more accessible, transparent, and open.

Reflecting My Time at Avebury

I have found my time very enriching to my experience as an archaeology student. At first, I found myself floundering (and at times, I still feel that way) with how vast the archive is, and the sometimes oppressive nature of searching through excel spreadsheets and google drives of JPGs. However, as the placement progressed, I have begun to embrace the openness of the archive and find myself happily, and aimlessly, scrolling through areas of interest.

Every day I work in the archives I am met with a new challenge to face. One such challenge is just how truly large it is. It is home to thousands of photographs of actual artifacts, but also landscape photography, feature photography, and photographs of diaries. Because of this, it can be difficult to navigate, especially when contending with filtering between excel sheets listing the accession numbers of artifacts, and the google drive files. It is no easy task to familiarize yourself with the many different accession numbers and associated codes for different artifacts, but it is necessary to do – especially if you hope to find the patterns and themes within the archive to build something like a Pathway as I was asked to do.

The upside to a challenge such as this, however, is the feeling of triumph after choosing a theme and following it through the archive. And who really minds looking at the rich history that lives within the archive? After many hours of taking note of accession numbers, similar photographs and key words in diaries, certain patterns begin to emerge – which is precisely how my Pathway was born!

It is challenges like this that made the experience at Avebury exactly what I was hoping for: a way to build my skills as a digital archaeologist by teaching me the best ways to navigate an archive, and how to use an archive to bring it to the outside world so others can enjoy it as I have.