Visitors to Avebury recently may have witnessed the odd sight of two people walking around with cameras on the end of long poles. Certainly, many people came up to ask what we were doing, and no, it wasn’t part of a mysterious mid-summer ritual!

The truth is sadly more mundane. Adam Stanford of SUMO GeoSurveys (https://www.sumoservices.com/archaeology-geophysical) and I have been conducting a survey of the Avebury and West Kennet Avenue stones using a technique known as photogrammetry, a technique for generating 3d models of objects.

I should add that our survey happened to coincide with a period of beautiful sunny weather. The brilliant sunshine and strong shadow was far from ideal conditions for stone photography, but it was hard to worry about that as the buttercups were out and the West Kennet Avenue was looking rather magical!

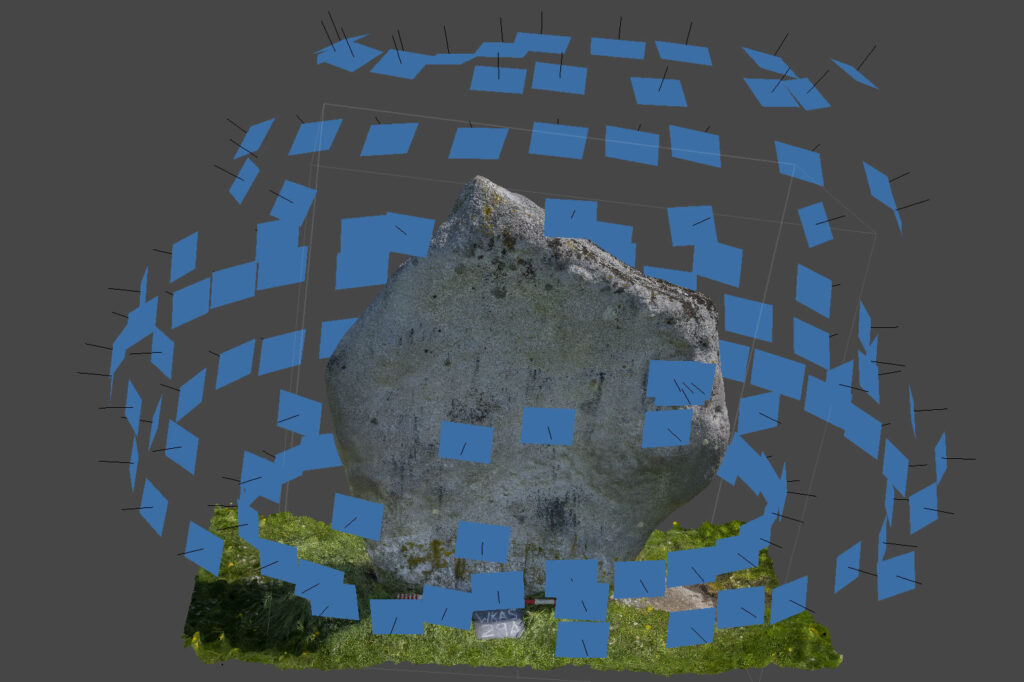

In order to make the photogrammetric model, we take overlapping photos of the stones from every possible angle (hence the long poles). This involved taking roughly 150 shots for each stone. Once the photographs have been taken, we use software to generate a 3d point cloud by triangulating the positions of individual points on a stone using multiple photographs taken from different angles.

The end result is an accurate 3d model of each stone.

Those of you that follow the Avebury Papers project will know that the focus of our project is on digitising the archive from Avebury’s 20th century excavations. Therefore, you are probably wondering why we want to survey the stones. The answer is a little convoluted.

The starting point is that there are lots of photographs of Avebury’s stones in the Keiller archive (we estimate there to be 2000 of them!). Many of these are only partial images of stones taken from odd angles as they were being uncovered, or re-erected, in the 1930s. It is quite difficult to identify which stones appear in the photographs but this is information that we would very much like to add to our catalogue so that ultimately people will be able to search for all the images and written records associated with each individual stone on the site.

Whilst trying to work out how we were going to identify these stones, the opportunity came up to work with some clever people at the University of York involved with machine learning. They have set up a project that aims to teach a computer to identify the stones in the photographs for us. I won’t go into more detail here as this part of the project will be covered in detail in a future blog post. Suffice to say, the first step is to give the computer some images of Avebury’s stones to use as a reference point. These photos need to provide the computer data on what every stone looks like from every possible angle, and so the obvious starting point was to create a 3d model of the stones using photogrammetry. A few examples of what the models look like can be seen below.

AS-09 by SUMO GeoSurveys on Sketchfab

WKAS-35A by SUMO GeoSurveys on Sketchfab

Beyond teaching a computer to recognise a stone, there are many more reasons why the photogrammetric survey is a great idea.

First of all it will provide accurate 3d survey data that will be essential baseline data for the future management of the monument.

Secondly, the survey opens up lots of avenues for further research. For example, it will allow us to conduct a detailed quantified analysis of the surfaces of the stones. Many of the stones at Avebury have evidence of differing amounts of flaking and pecking of their surfaces. This is of interest as, unlike Stonehenge, Avebury’s stones are often thought of as being natural sarsen boulders that have not been dressed. We will use the photogrammetric model to try and work out how much of the surface alteration of the stones relates to the working of them in prehistory, as opposed to natural weathering, or medieval and later attempts to break or bury the stones.

Ultimately, we aim to survey the whole of the monument, including its banks and ditches. Once this has been done the model will also be able to quantify the volume of its earthworks to a higher level of accuracy than has previously been possible.

Alongside an improved understanding of the pecking and flaking of Avebury’s stones, this information will be an essential component in understanding the scale and complexity of the Neolithic construction of the monument.

For now, though, there is more survey work to be done. We estimate that we may need to take 15,000 photographs before we have captured every stone from every possible angle. So you may well see more people wandering around with cameras on poles in the months to come!