Hello world! Below you will find our first press release – we hope the first of many exciting updates. Share the news, and follow this blog for more.

Bournemouth University, University of York, The National Trust, the Archaeology Data Service, Historic England, and English Heritage.

Update: January 2024: University of Bristol replaces Bournemouth University as a project partner, as the home institution of the project Principal Investigator.

A project is underway to bring 5,000 years of history to life at Avebury World Heritage site.

A team of experts from Bournemouth University, the University of York, the Archaeology Data Service, and the National Trust, with support from Historic England and English Heritage, are creating a public, open access digital archive of Avebury, and the archaeological discoveries made there.

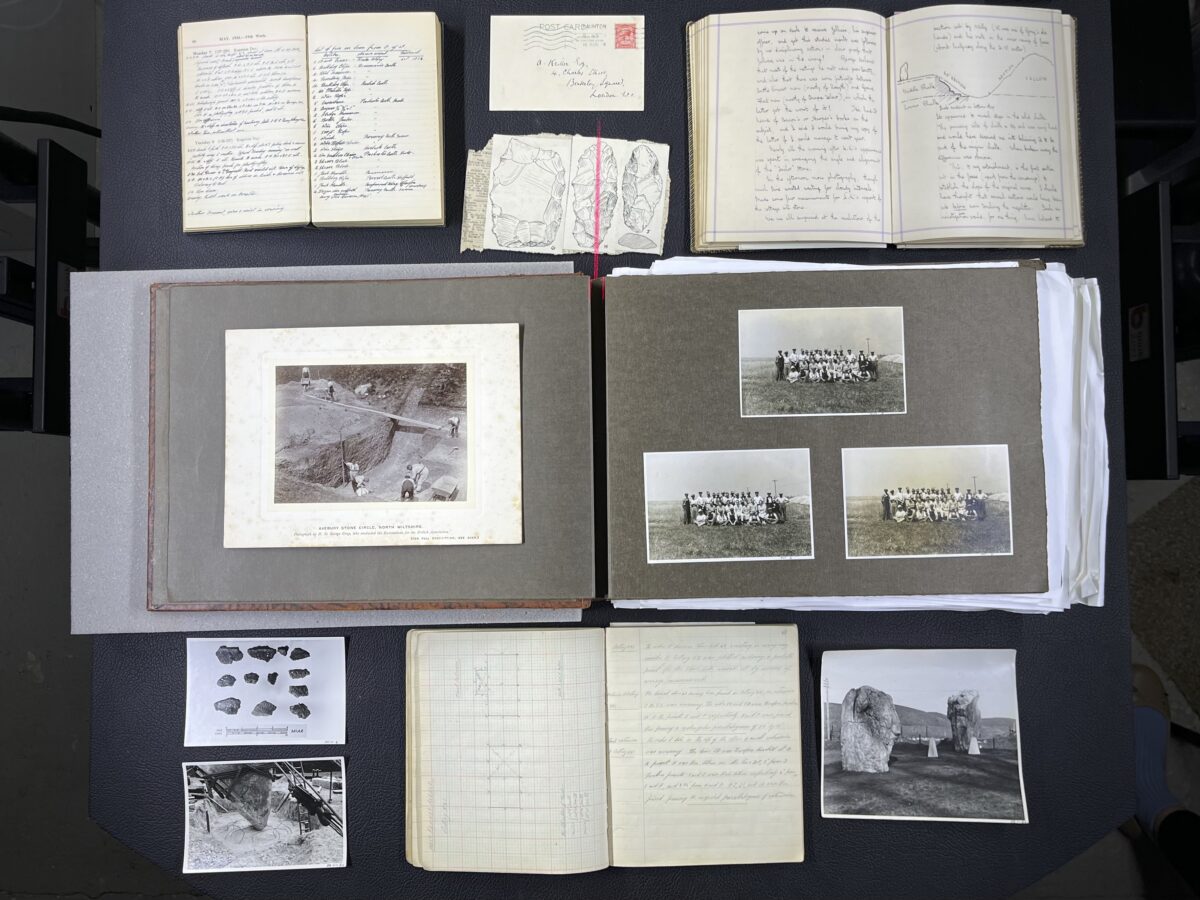

Professor Mark Gillings (Bournemouth University) and Dr Colleen Morgan (University of York) have been awarded £804,142 by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) for ‘The Avebury Papers’. This four-year project will analyse, expand, digitise, and share Avebury’s unique multimedia archive, detailing its Neolithic origins and its subsequent life-history, from a medieval hamlet to a modern site of heritage, tourism, creativity, and spirituality.

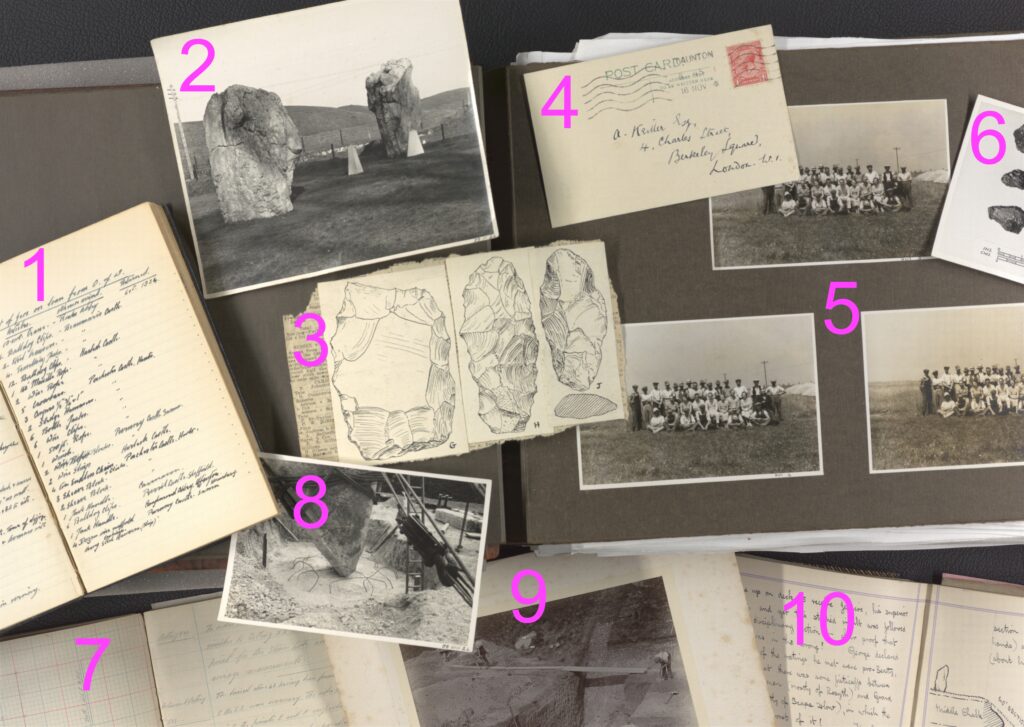

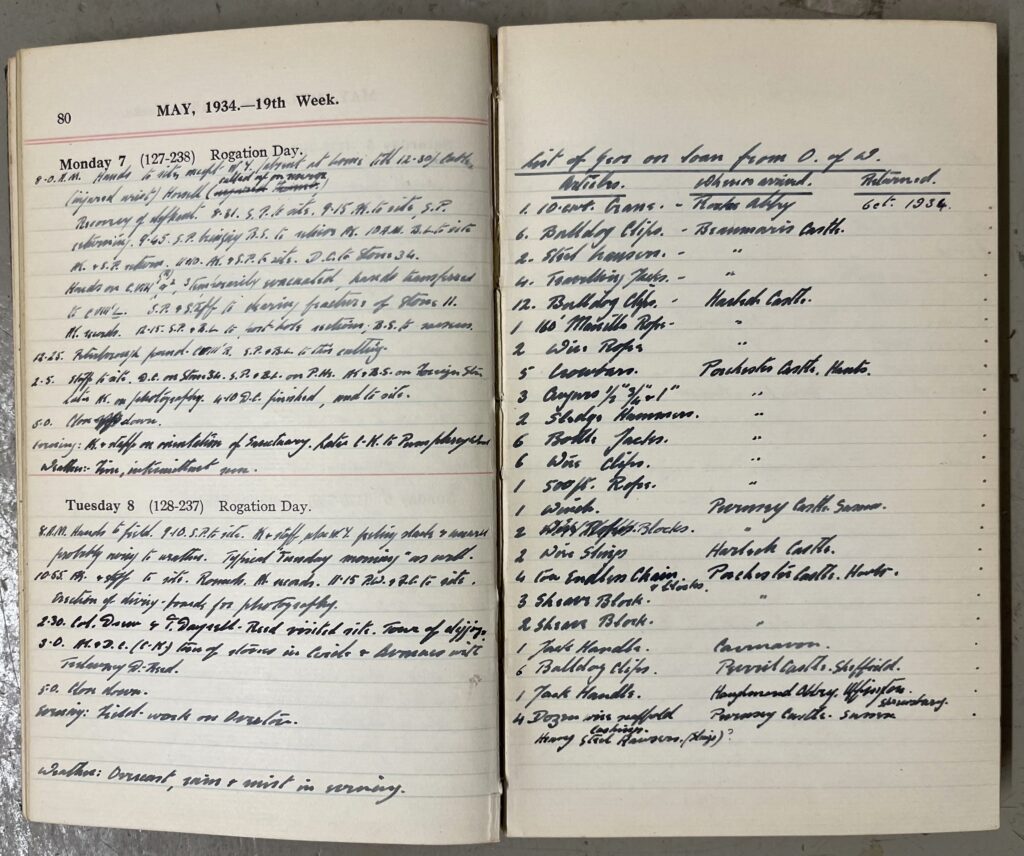

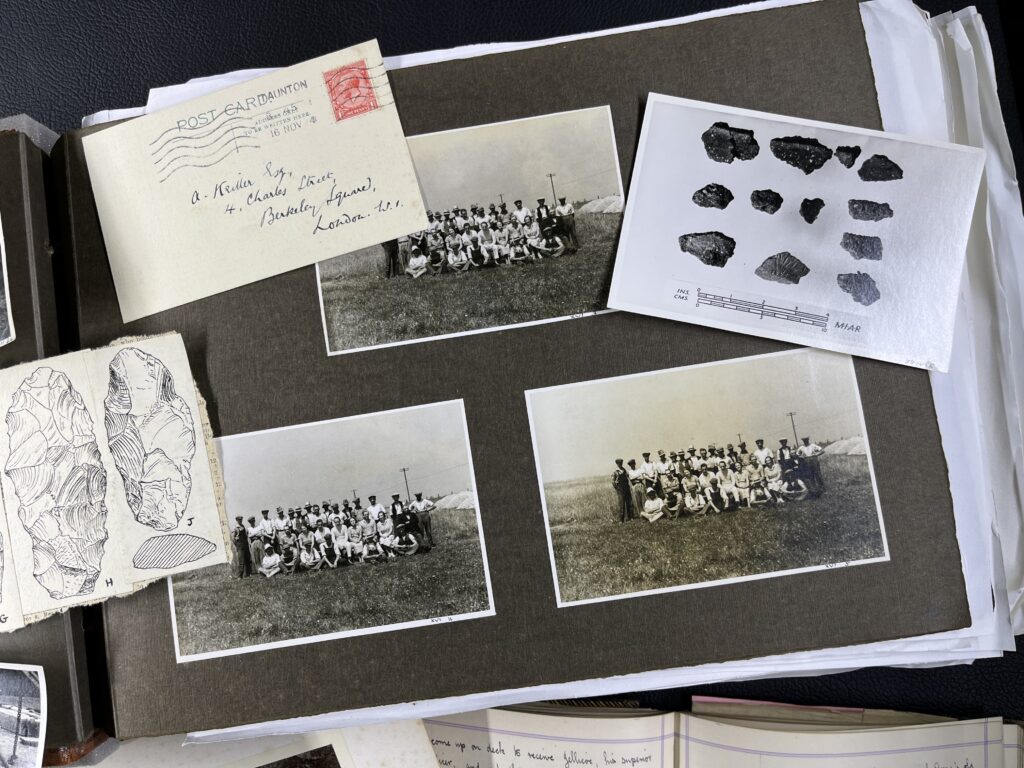

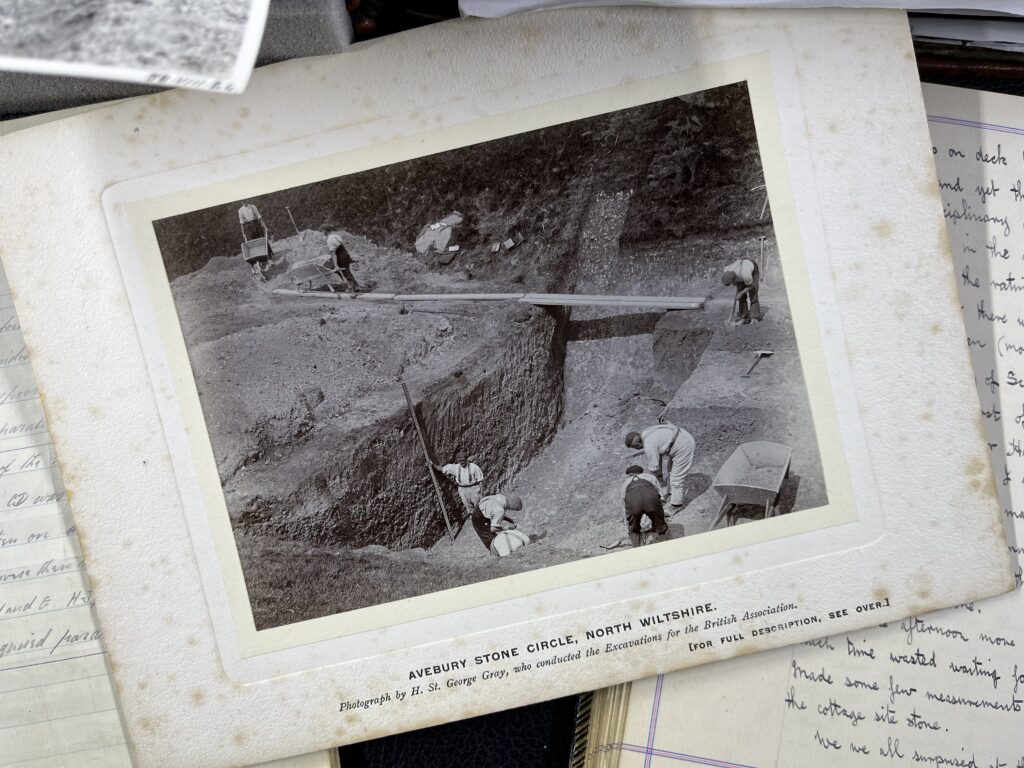

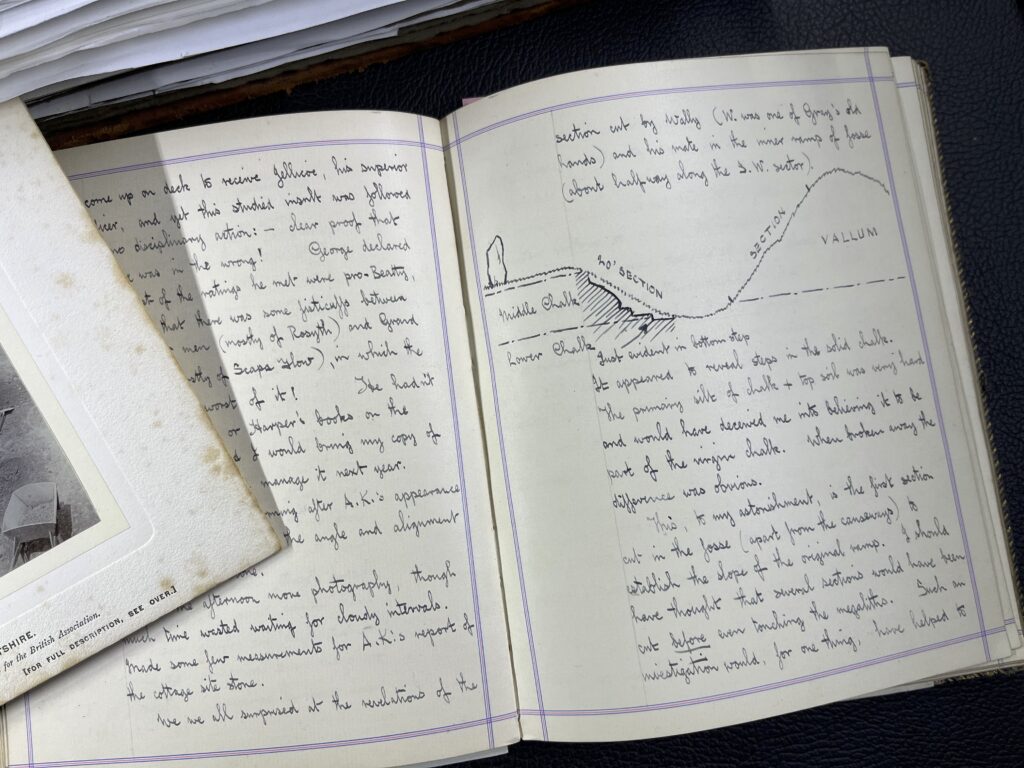

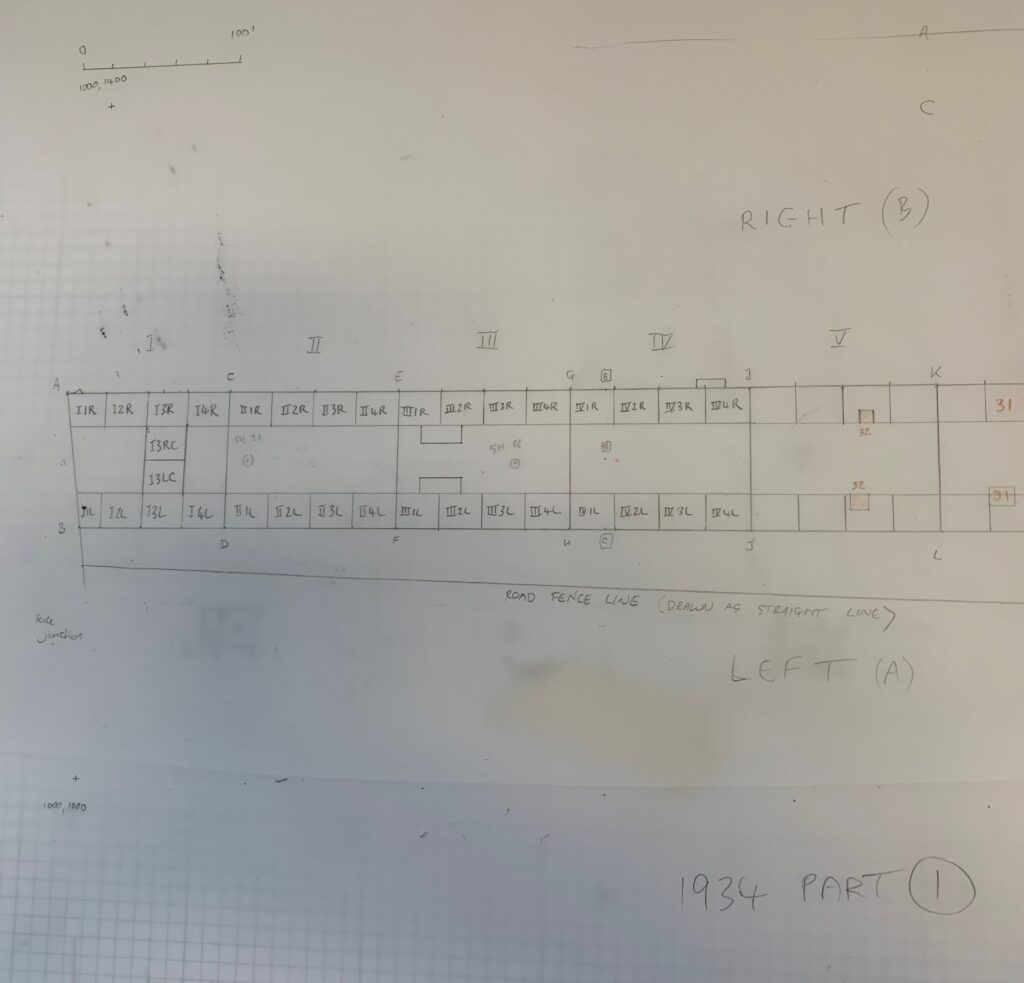

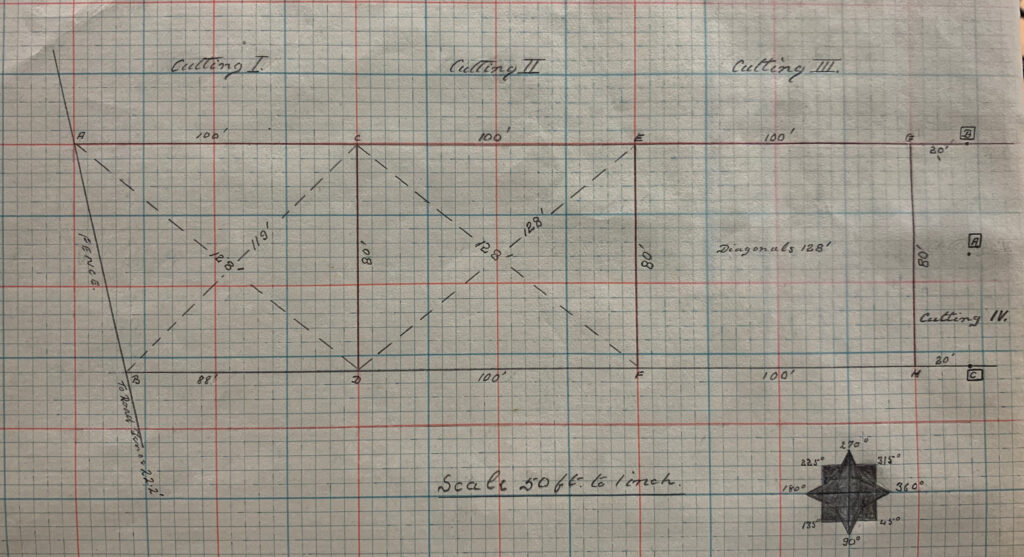

Currently dated to the first half of the 3rd Millennium BCE, the megalithic monuments at Avebury, North Wiltshire, form part of the UNESCO Stonehenge and Avebury World Heritage Site. Avebury comprises one of the UK’s largest Henge monuments, containing the world’s largest stone circle at almost 350m in diameter, with avenues of paired standing stones that extend out into the landscape for 3.5km to link Avebury to a host of other important prehistoric structures. Alexander Keiller led archaeological excavations at Avebury in the 1930s, and the documents and finds from this period – which are now held at the Alexander Keiller Museum – are the core of the Avebury Papers project.

Professor Gillings said: “Despite its international importance, the only large-scale archaeological excavations to take place at Avebury were concluded just before the outbreak of WWII. Whilst a masterful summary of the results of this work was produced in the 1960s, the incredible detail they revealed has remained unstudied and unpublished”.

The Avebury Papers project will add to the archaeological work that was ended abruptly by the outbreak of war, bringing together and contextualising not only the findings from the 1930s work and other 20th century interventions, but also exploring the lives of the people and organisations that made the work possible. Importantly, the entire archive will be made available online on an ‘open access’ basis for anyone to use for research, enjoyment, and artistic projects.

The Avebury estate was sold to the National Trust by Alexander Keiller and the monument placed in the Guardianship of the state in 1944. Some years later in 1966, the collection of the Alexander Keiller Museum was given to the nation by Gabrielle Keiller, Alexander Keiller’s widow. Overarching responsibility for the collection and the paper archives now lies with Historic England, on behalf of the nation. Historic England’s national collection of historic sites and artefacts is managed by the English Heritage Trust and at Avebury the Alexander Keiller collection is on loan from English Heritage to the National Trust, who own and operate the site.

Avebury’s significance extends far beyond the British Isles, informing research on a range of fundamental questions concerning the European Neolithic, such as why and how people went to the trouble of building such vast monuments. By providing a fuller understanding of the history of this World Heritage Site, this research and the multimedia digital archive it will generate will enable more effective heritage management, education, and tourism programmes. The project will therefore bring enormous benefit to visitors, enthusiasts and students of prehistory, artists, and heritage organisations, telling the full story of the origins and re-use of Avebury across over 5,000 years.

Notes to editors

The Avebury Papers is a four-year project to analyse, expand, digitise, and share the unique archive related to the Neolithic Avebury site, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council. The research team comprises Principal Investigator Professor Mark Gillings (University of Bournemouth), Co-Investigator Dr Colleen Morgan (University of York), Dr Ben Chan (University of Bournemouth) and Dr Fran Allfrey (University of York), in collaboration with Dr Rosamund Cleal (The National Trust), and the Archaeology Data Service, supported by Historic England and English Heritage.

About the National Trust Wiltshire Landscape

The National Trust looks after approximately one-third of the Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites World Heritage Site, which is recognised as internationally important for its complexes of outstanding prehistoric monuments.

Avebury: The National Trust cares for around 650 hectares of this outstanding prehistoric landscape as well as many of the major monuments within it. These monuments include Avebury Henge and Stone Circles – the largest stone circle in the world, West Kennet Avenue, Windmill Hill and many Bronze Age barrows. For more information visit www.nationaltrust.org.uk/avebury.

Stonehenge Landscape: The National Trust cares for around 850 hectares of the fragile and archaeologically rich landscape around Stonehenge which includes globally significant monuments such as Durrington Walls, the Stonehenge Cursus and the Stonehenge Avenue. This landscape is recognised for its Neolithic and Bronze Age archaeology reflecting past ceremonial practices. For more information visit www.nationaltrust.org.uk/stonehenge-landscape.

Wiltshire Countryside: The National Trust looks after a number of special countryside sites which are particularly precious for their rare and protected wildlife, natural beauty and archaeological importance. We work to maintain and improve these fragile natural habitats. Our sites include Figsbury Ring, The Coombes at Hinton Parva, Calstone and Cherhill Downs, Lockeridge Dene and Piggledene, Sutton Lane Meadows, Pepperbox Hill, White Barrow and Cley Hill. These can all be seen at www.nationaltrust.org.uk/wiltshire-landscape.

About the National Trust

The National Trust is a conservation charity founded in 1895 by three people: Octavia Hill, Sir Robert Hunter and Hardwicke Rawnsley, who saw the importance of the nation’s heritage and open spaces and wanted to preserve them for everyone to enjoy. Today, across England, Wales and Northern Ireland, we continue to look after places so people and nature can thrive.

The challenges of the coronavirus pandemic have shown this is more important than ever. From finding fresh air and open skies to tracking a bee’s flight to a flower; from finding beauty in an exquisite painting or discovering the hidden history of a country house nearby – the places we care for enrich people’s lives.

Entirely independent of Government, the National Trust looks after more than 250,000 hectares of countryside, 780 miles of coastline and 500 historic properties, gardens and nature reserves.

The National Trust is for everyone – we were founded for the benefit of the whole nation. We receive on average more than 26.9 million visits each year to the places we care for that have an entry fee, and an estimated 100m visits to the outdoor places that are free of charge. Paying visitors, together with our 5.6 million members and more than 53,000 volunteers, support our work to care for nature, beauty, history. For everyone, for ever.

About Historic England

We are Historic England, the public body that helps people care for, enjoy and celebrate England’s spectacular historic environment, from beaches and battlefields to parks and pie shops. We protect, champion and save the places that define who we are and where we’ve come from as a nation. We care passionately about the stories they tell, the ideas they represent and the people who live, work and play among them. Working with communities and specialists we share our passion, knowledge and skills to inspire interest, care and conservation, so everyone can keep enjoying and looking after the history that surrounds us all.

About English Heritage

English Heritage cares for over 400 historic buildings, monuments and sites – from world-famous prehistoric sites to grand medieval castles, from Roman forts on the edges of the empire to a Cold War bunker. Through these, we bring the story of England to life for over 10 million people each year. Registered charity no. 1140351 www.english-heritage.org.uk

Media Contact Details

Bournemouth University

Department of Archaeology and Anthropology

Bournemouth University, Talbot Campus, Poole, Dorset, BH12 5BB, UK

Email: newsdesk@bournemouth.ac.uk

Tel: +44 (0)7715 812218

University of York

Department of Archaeology

University of York, King’s Manor, York, YO1 7EP, UK

Email: archaeology@adminTel: +44 (0) 1904 323972