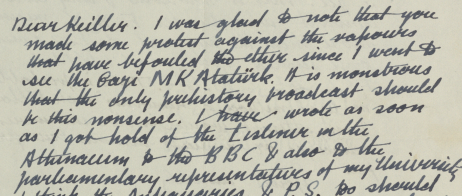

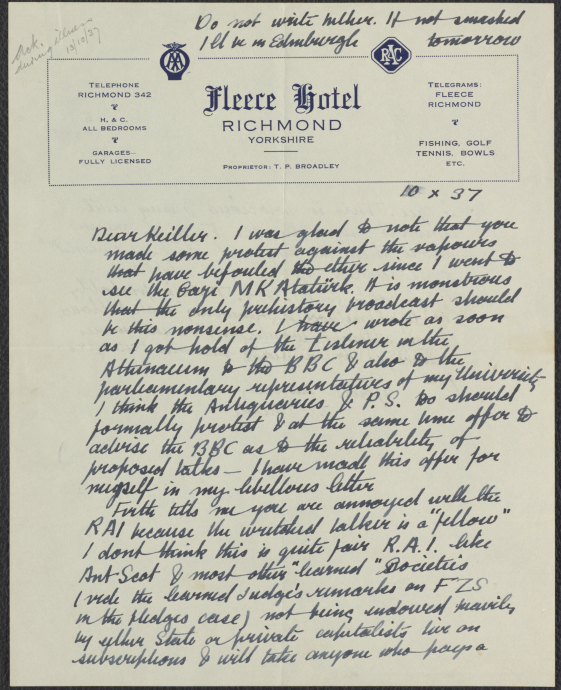

“I was glad to note that you made some protest against the vapours that have befouled the ether […] it is monstrous that the only prehistory broadcast should be this nonsense.”

– V Gordon Childe to Alexander Keiller, 10 October 1937

On Friday 17 September, 1937, BBC Radio aired one of a three-part series titled, “The Unchronicled Past” by antiquarian John Foster Forbes. Foster Forbes was dedicated to the idea that megaliths were built by the survivors from Atlantis. He was noted for his opinions on UFOs, giants, and psychometry, which was the practice of feeling and studying vibrations from ancient monuments. The inclusion of his ideas on BBC Radio sparked vociferous protest from contemporary archaeologists: including Alexander Keiller and V Gordon Childe, who was then Abercromby Professor of Archaeology at University of Edinburgh. For an excellent further discussion of BBC Radio and archaeology, see Jan Lewis’ 2021 PhD.

Fran and her team of digitising volunteers at Avebury came across materials in the archive that demonstrate push-back from archaeologists regarding unorthodox ideas about the past, and show how scholarly debate filtered into the mainstream.

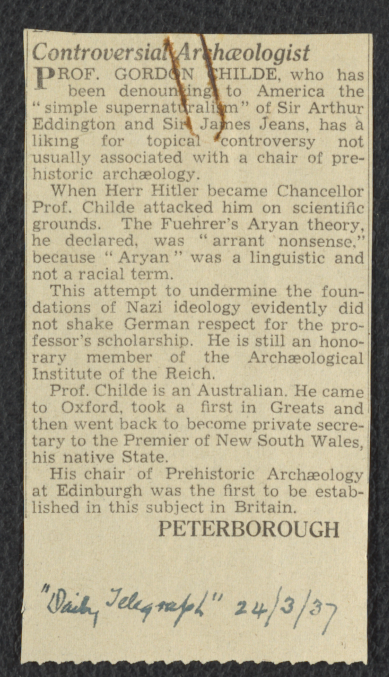

A March 1937 clipping in the Daily Telegraph calls Childe a “Controversial Archaeologist” for denouncing the “simple supernaturalism” of physicists Sir Arthur Eddington and Sir James Jeans, and for calling Hitler’s Aryan theory “arrant nonsense”.

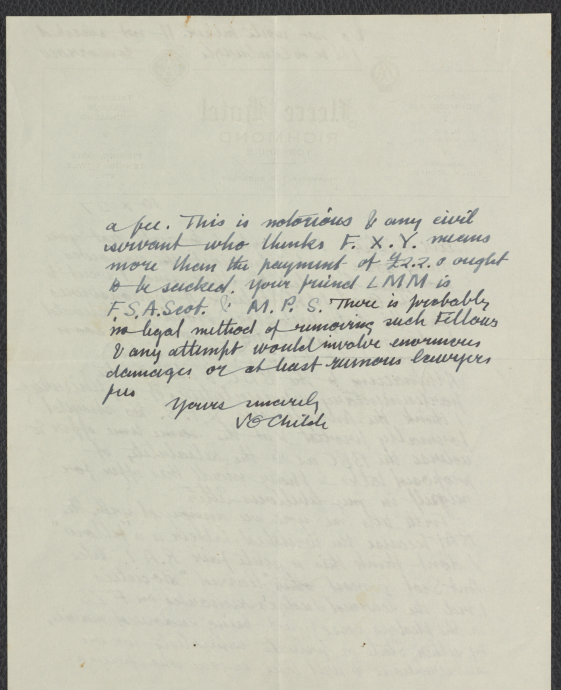

A 10th October letter from Childe to Keiller, containing the assessment of the “befouling vapours” of Foster Forbes’ theories, was sent on stationery from the Fleece Hotel in Richmond, Yorkshire, which is still a going concern. He rails against Foster Forbes’ appearance on BBC Radio, “It is monstrous that the only prehistory broadcast should be this nonsense.” He rallies archaeology’s institutions to protest and to “offer to advise the BBC as to the reliability of proposed talks” and complains about the admission of “any civil servant” to learned archaeology societies.

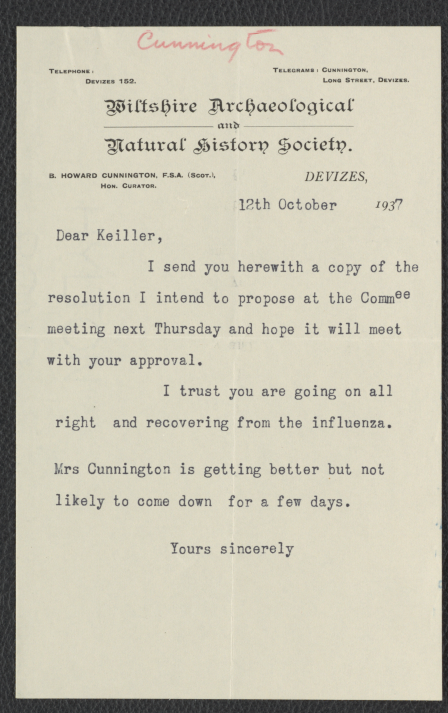

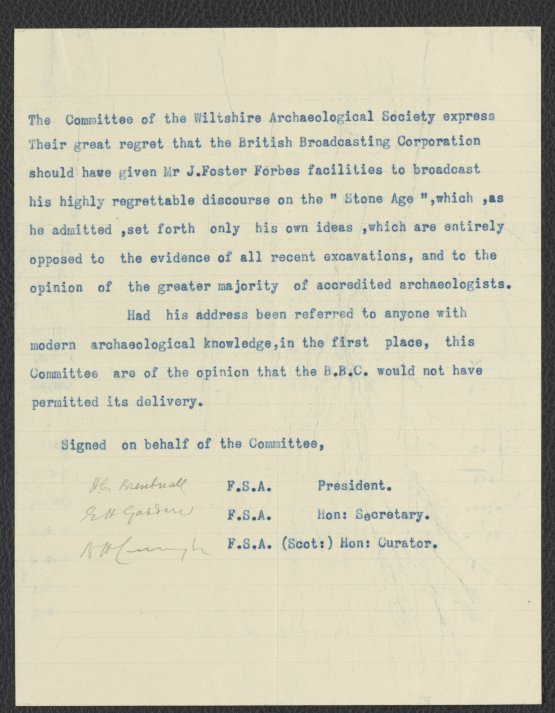

Howard Cunnington, curator for the Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society (WANHS), writes to Keiller on the same topic a couple days later. He attaches a resolution he was to put forth at the WANHS committee meeting, which expresses concern that the BBC had broadcast Foster Forbes’ “highly regrettable discourse on the ‘Stone Age’, which, as he admitted, set forth only his own ideas, which are entirely opposed to the evidence of all recent excavations, and to the opinion of the greater majority of accredited archaeologists”.

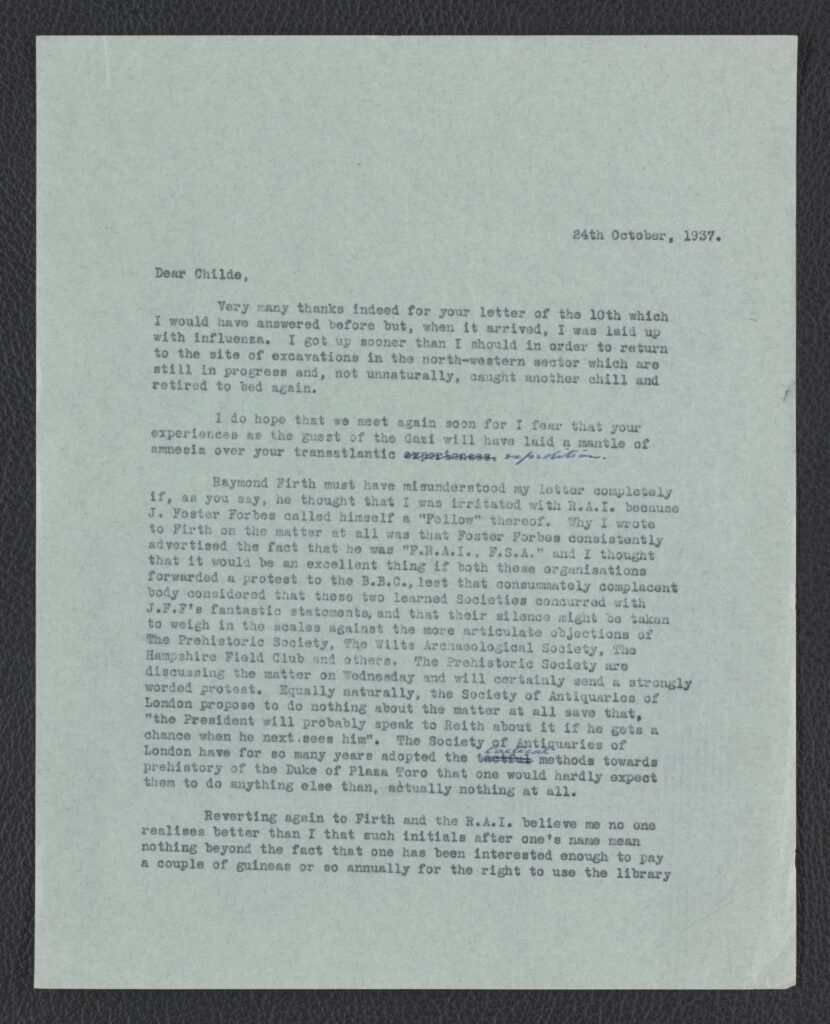

In Keiller’s reply to Childe (sent two weeks later, as he was suffering with flu), he echoes Childe’s complaint regarding the membership of Foster Forbes to the Royal Anthropological Institute and the Society of Antiquaries, and notes that he has suggested that both societies distance themselves from Foster Forbes’ views. He explains how The Prehistoric Society, WANHS, the Hampshire Field Club, and others have already made “articulate objections”.

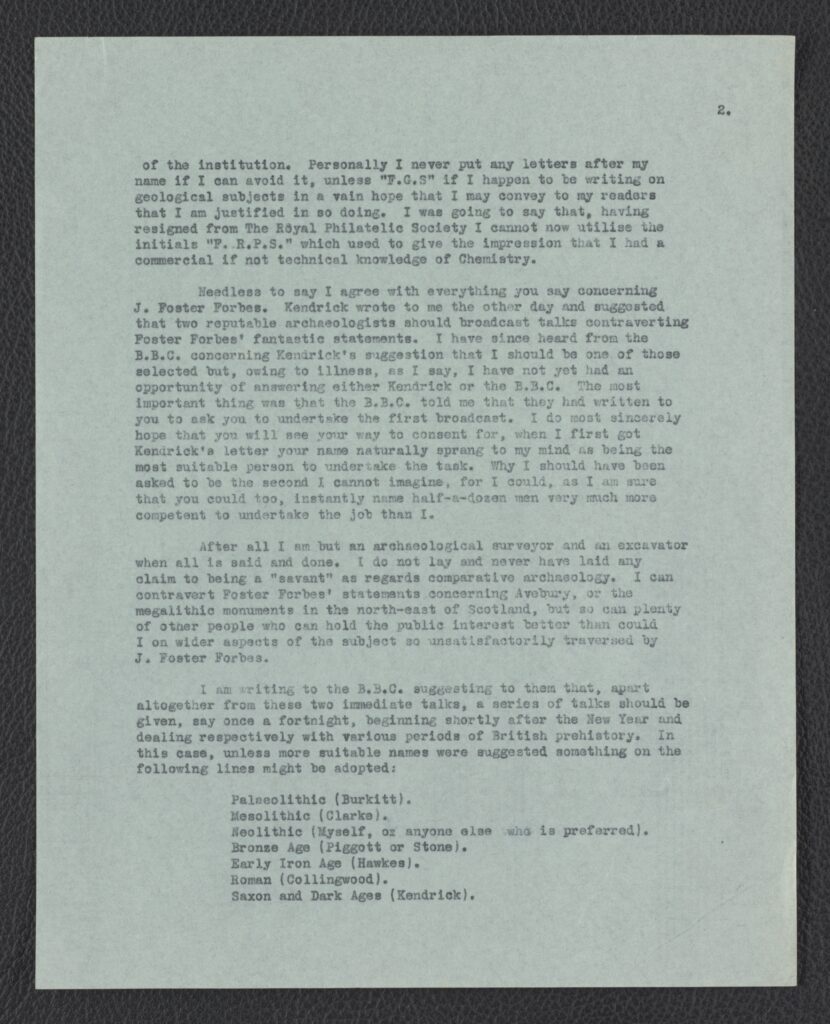

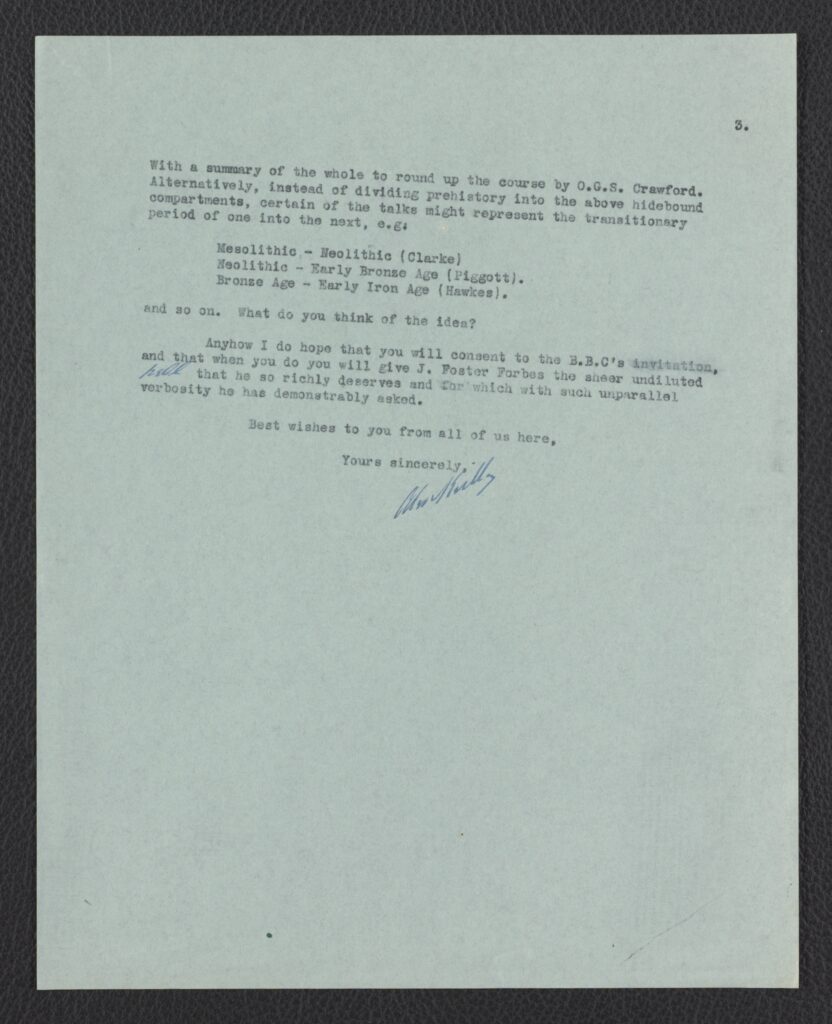

Keiller also reveals how Kendrick (T D Kendrick, keeper of British and Medieval Antiquities at the British Museum) had written to him to suggest that “two reputable archaeologists should broadcast talks controverting Foster Forbes’ fantastic statements”. Modestly, Keiller suggests that he might “instantly name half-a-dozen men very much more competent to undertake the job than I. After all I am but an archaeological surveyor and an excavator when all is said and done”. Keiller duly appends a list of archaeological subjects and specialists including Grahame Clarke, “Hawkes” (probably Christopher, perhaps Jacquetta – both had contributed to BBC programming previously), R G Collingwood, O G S Crawford, and Stuart Piggott to propose to the BBC, asking Childe what he thinks to the idea.

There are several more letters back and forth between Keiller and Childe, and others, on Foster Forbes. These clippings and letters in the Avebury archive reveal Keiller and later curators’ interests in preserving discussions about archaeology as much as the physical archaeology. They show how networks of peers could be mobilised to defend – or gatekeep, depending on whose side you are on – archaeological narratives.

Over 80 years later, archaeologists are still mounting campaigns against what is commonly called “pseudoarchaeology”. Graham Hancock’s popular Ancient Apocalypse aired on Netflix in 2022, rehearsing some of the ideas Foster Forbes put forth regarding ancient people, aliens, and Atlantis.

John Hoopes, Flint Dibble, and Carl Feagans responded to this programme in the Society for American Archaeology journal, noting that by addressing pseudoarchaeology, archaeologists are “damned if we do and damned if we don’t” as some people argue that interacting with the theories – even to denounce them – adds legitimacy and visibility. Hoopes, Dibble, and Feagans record the various public-facing, social media, and popular media attempts to refute Hancock. Lobbying for a BBC series on the matter – as per Keiller’s suggestion – just would not reach the same audience as in 1939, as pseudoarchaeologies multiply across global, digital spaces.

Indeed, these theories seemingly hold enormous sway in public imaginaries. Alongside attempting to myth-bust, it is therefore vital to consider why these myths take root. During the recent Radio 4 ‘In our time’ discussion on megaliths, Melvin Bragg was audibly exasperated with the expert response to many questions of ‘we can’t know for sure’: archaeological myths play a powerful role creating and sustaining interest in ancient places, and go far beyond any individual or learned institution’s control.

After speaking about the Avebury Papers on the radio, Colleen received a pamphlet regarding an alternate theory regarding Avebury involving ley lines. She emailed the author back and invited him to come to Avebury, perhaps to volunteer or just to have a chat. He was incredibly lovely, and declined, as he was very elderly and taking care of his partner. We hope he keeps in touch and we will share the online archive with him when it is available.

These enthusiasts are stakeholders in the Avebury Papers, and as a project team we are still trying to understand their interests and needs in our outreach and care of the digital archive. We hesitate to dismiss their attachment to Avebury as unimportant or irrelevant. Can we form an inclusive archive when these divisions have defined archaeology for decades? Or can we conceive of the Avebury Papers digital archive as an opportunity for reconciliation, de-escalation, and an invitation in?