Choosing a photograph for the homepage of this website was tricky. We wanted something that would represent a wide selection of items held at the Alexander Keiller Museum, while taking conservation requirements into account.

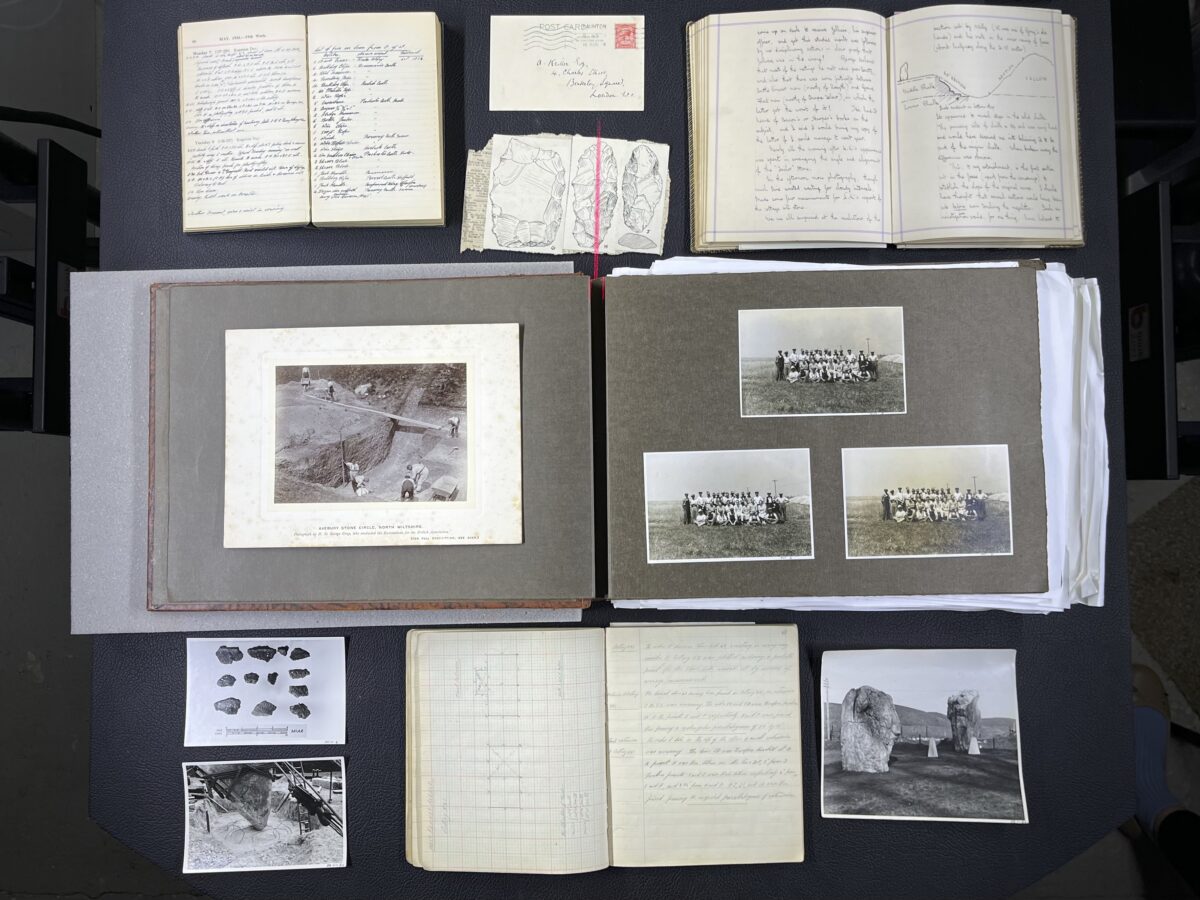

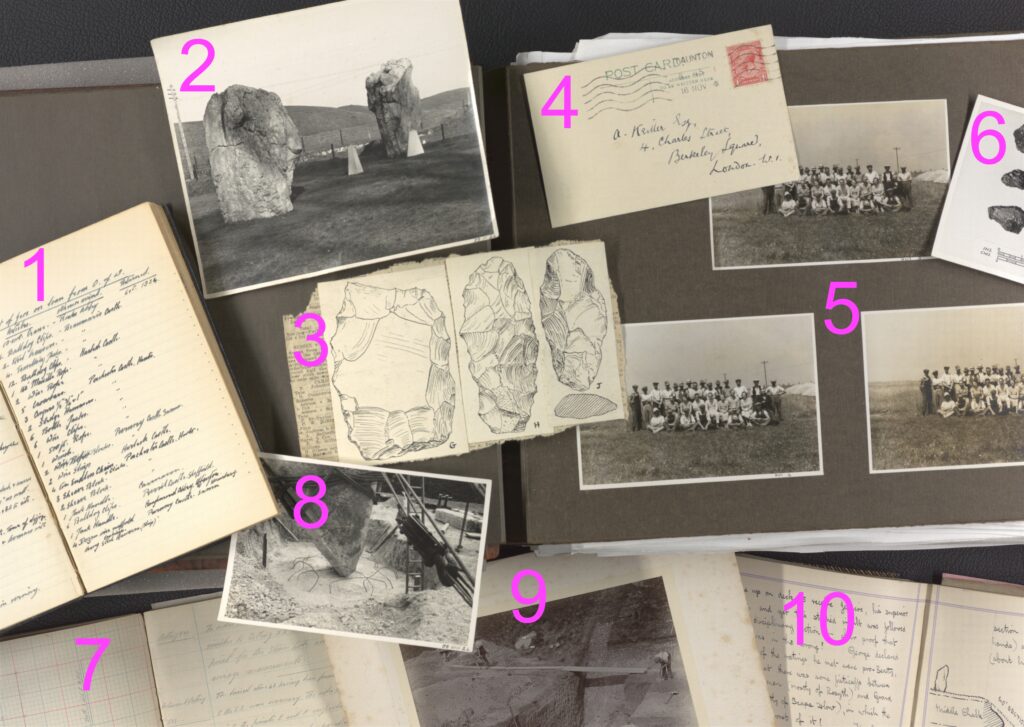

So, while we couldn’t mix paper and artefacts, we went for a selection of photographic prints, letters, diaries, and archaeological drawings.

Here’s what you can see on the Avebury Papers homepage, starting from the top left item working across, with further details about each item…

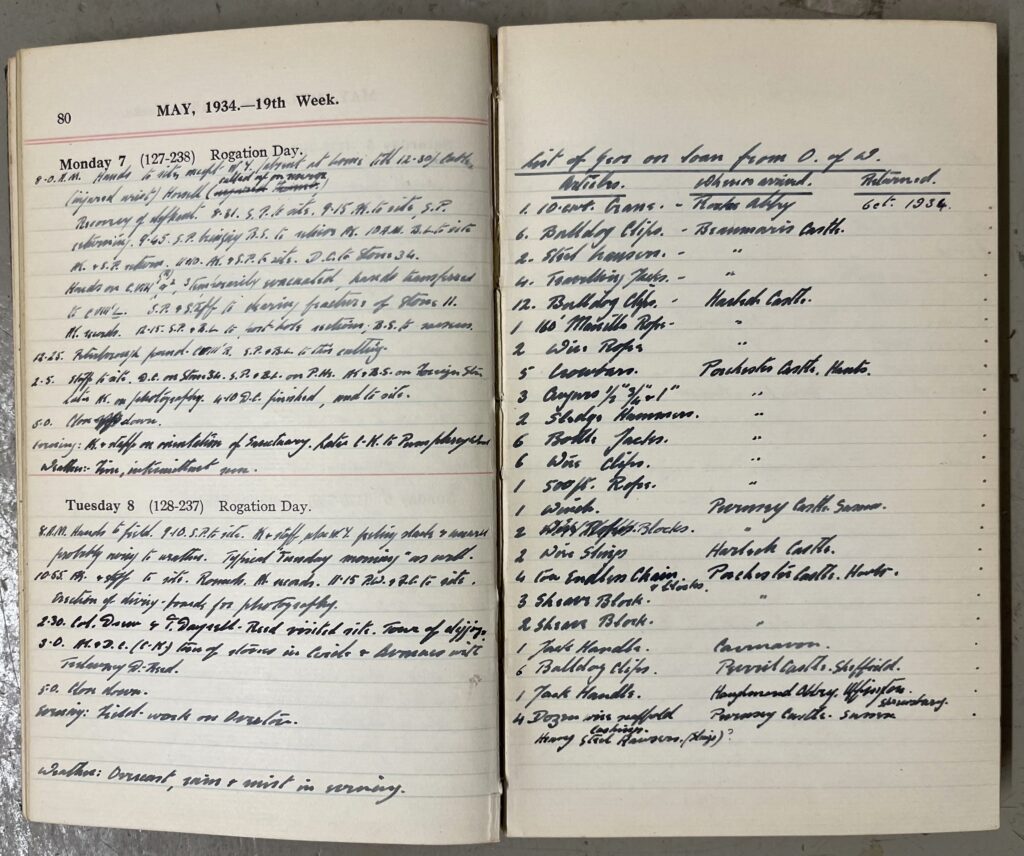

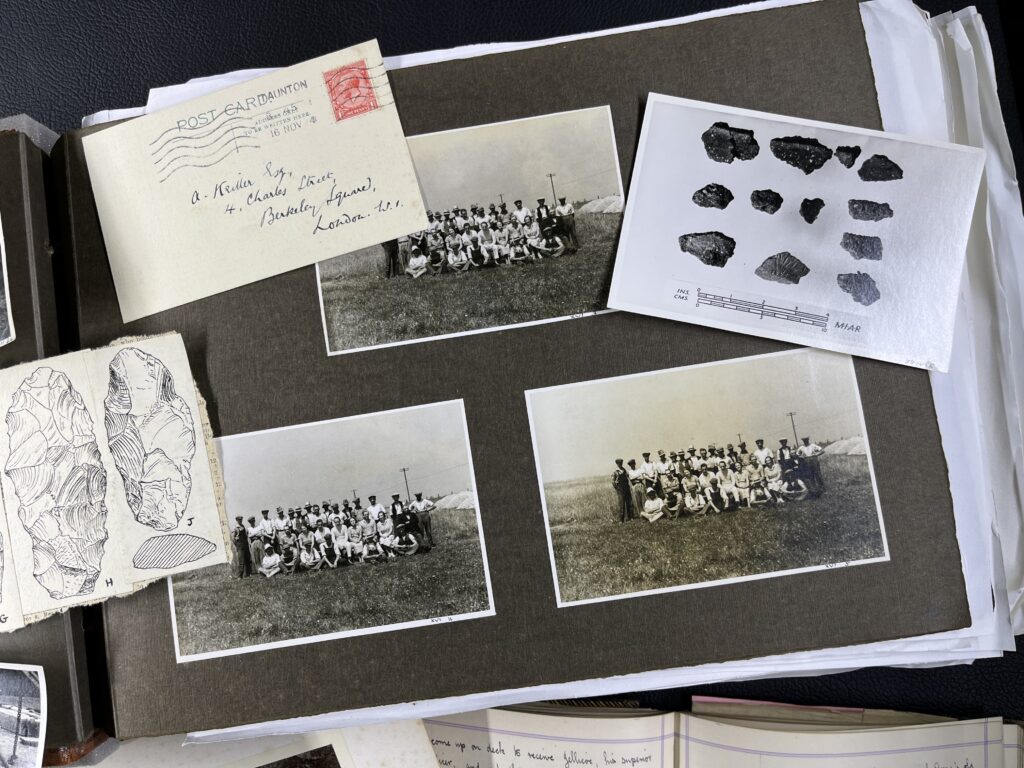

1. West Kennet Avenue Excavation Diary, 1934, accession number 78510467. Alexander Keiller and his team kept meticulous records during their excavations. We wanted to show an example of Keiller’s handwriting, and here we’ve opened the diary at a spread which shows a day entry on the left, and a list of gear loaned from ‘O of W’ (Office of Works) on the right. By the end of this project, handwritten diaries will be transcribed and searchable.

2. A black and white print from 1939 of two standing stones, and two newly installed ‘obelisks’ to mark lost stones, with an early 20th century photograph number 39II24.

3. Three pen-and-ink drawings of flints, possibly made by H G O Kendall at Grimes Graves. These three drawings are pasted onto newspaper, and there are 84 such collages that are collectively accessioned to 88051603.

4. A postcard addressed to Alexander Keiller’s Berkeley Square home, with a postmark of 16 November 1924, accessioned with letters to Keiller at 78510455.

5. Photo Album A, open at page ‘000’, showing the West Kennet Avenue staff team in 1934, accession number 78510300. A key aim of the Avebury Papers is to identify these people and gather biographical information. Do you recognise anyone?

6. A photographic print of a flat lay of pottery dated to 1939, and accessioned with an early 20th century photograph number 39IV5. The letters ‘MIAR’ in the bottom right of this image stand for Morven Institute of Archaeological Research, the business that Keiller established for carrying out his archaeological activities.

7. The 1934 West Kennet Avenue excavations plotting book, accession number 78510469. The book is open at a spread showing – in very faint pencil – Keiller’s record of ‘Cutting XXI’. Today, we’d call a ‘cutting’ a ‘trench’. Keiller was idiosyncratic in how he extended trenches, sometimes adding ‘squares, rectangles, or parallelograms of extension’. In order to accurately map Keiller’s measurements onto a precise location, Mark has his work cut out translating imperial and analogue to digital and metric! You can read more about this activity in Mark’s blog series.

8. A stone supported by ropes and props, waiting for concrete to be poured at the base. The excavation staff devised pulley systems to support the megaliths as they were heaved from the ground and re-erected. This photo is dated to 1938, and accessioned with an early 20th century photograph number 38VIII24.

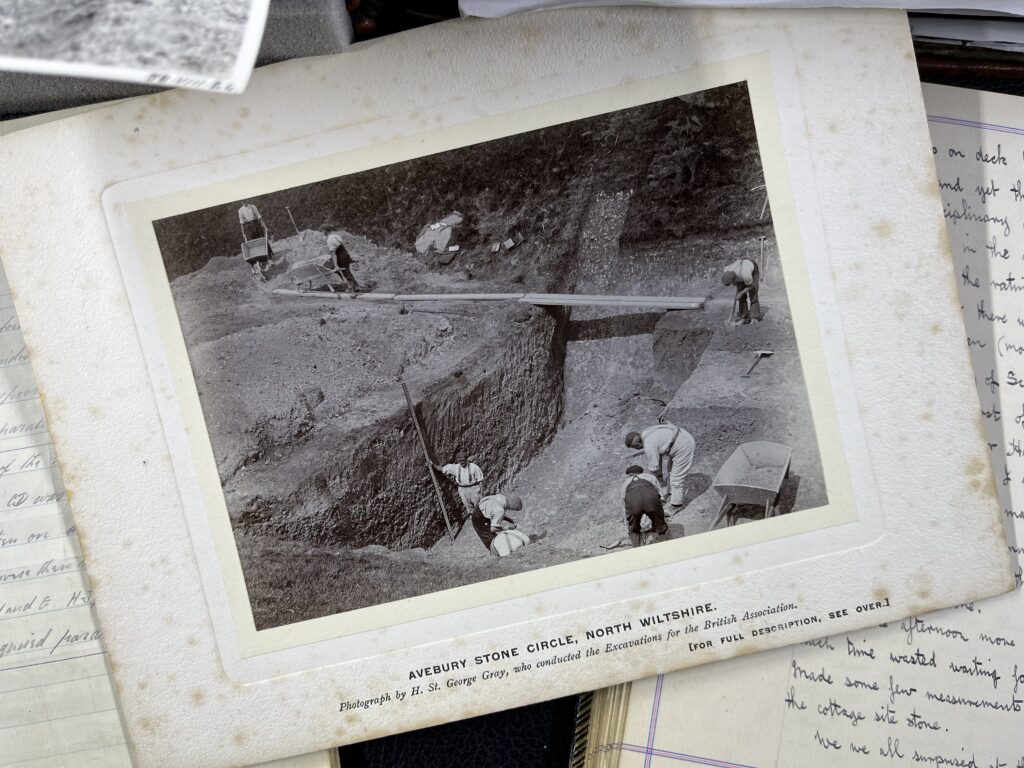

9. Workers excavating the ditch at Avebury, directed by Harold St George Gray for the British Association. The photograph was possibly taken by Gray, and is dated to 1908, with the accession number AVBAKP10.

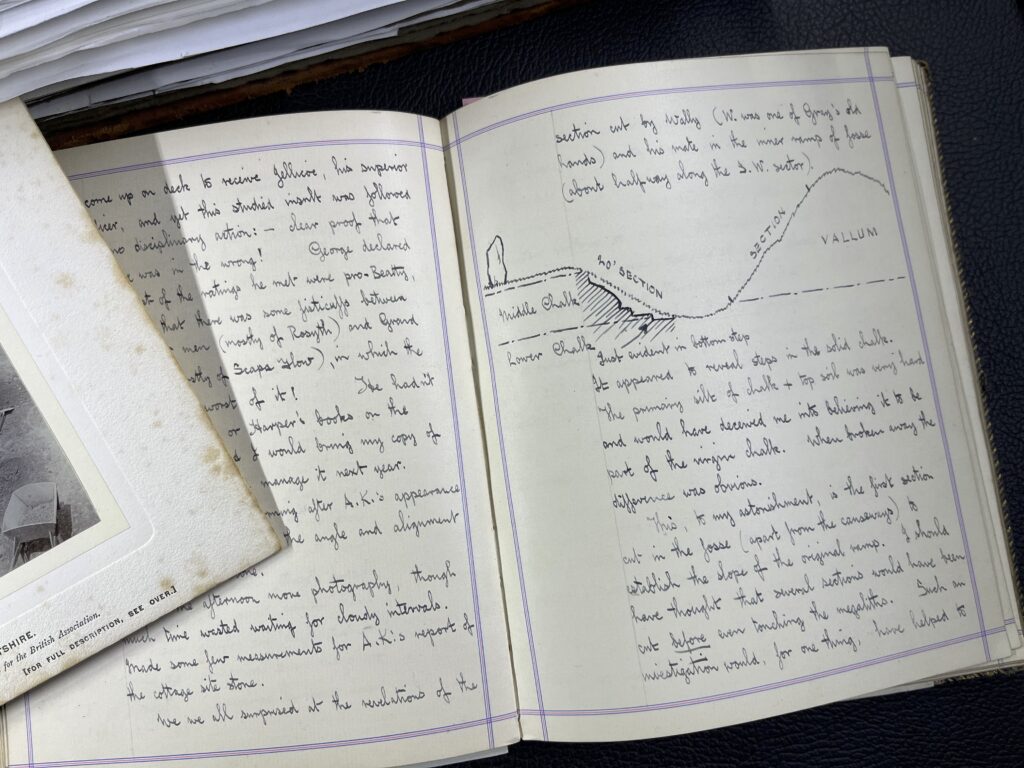

10. Denis Grant King diary from Wednesday 31 August 1938, accession number 20001093. Grant King kept beautifully illustrated diaries, which add detail to 1930s Avebury. He was an accomplished archaeological draftsman, and his plans, sections, and drawings from the 1930s further make up a meticulous record of the excavations and findings.